Audit of the Emergency Management Assistance Program

Date : April 2013

Project No. 12-08

PDF Version (195 Kb, 33 Pages)

Table of contents

Acronyms

| AASB |

Audit and Assurance Services Branch |

|---|---|

| AANDC |

Aboriginal Affairs and Northern Development Canada |

| DFAA |

Disaster Financial Assistance Arrangements |

| EMD |

Emergency Management Directorate |

| EMA |

Emergency Management Assistance |

| EMO |

Emergency Management Organization |

| NEMP |

National Emergency Management Plan |

| SOREM |

Senior Officials Responsible for Emergency Management |

Key Definitions

| Emergency management: |

The prevention and mitigation of, preparedness for, response to and recovery from emergencies. |

|---|---|

| Prevention/ mitigation: |

Actions taken to eliminate or reduce the risks of disasters in order to protect lives, property, the environment, and reduce economic disruption. Prevention/mitigation includes structural mitigative measures (e.g. construction of floodways and dykes) and non-structural mitigative measures (e.g. building codes, land-use planning, and insurance incentives). Prevention and mitigation may be considered independently or one may include the other. |

| Preparedness: |

Actions taken to be ready to respond to a disaster and manage its consequences through measures taken prior to an event, for example, emergency response plans, mutual assistance agreements, resource inventories and training, equipment and exercise programs. |

| Response: |

Actions taken during or immediately before or after a disaster to manage its consequences through, for example, emergency public communication, search and rescue, emergency medical assistance and evacuation to minimize suffering and losses associated with disasters. |

| Recovery: |

Actions taken to repair or restore conditions to an acceptable level through measures taken after a disaster, for example, return of evacuees, trauma counseling, reconstruction, economic impact studies and financial assistance. There is a strong relationship between long-term sustainable recovery and prevention and mitigation of future disasters. |

Executive Summary

Background

AANDC's Emergency Management Assistance (EMA) Program was formally established in 2005 and supports the legislative responsibilities placed on ministers to "identify risks that are within or related to their area of responsibility, to develop appropriate emergency management plans in respect of those risks, to maintain, test and implement the plans, and to conduct exercises and training in relation to the plans."Footnote 1 AANDC's role is to support the efforts of the primary provincial or territorial emergency management organizations in addressing emergency situations on-reserve that cannot be addressed by local communities on their own.

To ensure that First Nation communities have access to emergency assistance services which are comparable to those available to other residents in their respective provinces, AANDC enters into collaborative agreements with provincial governments for the provision of emergency services to First Nations communities, and provides funding to cover eligible costs. Presently, AANDC's EMA Program focuses predominantly on natural disasters (e.g. floods, storm surges, wild fires, etc.), search and rescue, and the failure of community infrastructure (i.e. critical roads, back-up power sources, bridges, etc.) due to natural disasters or accidents.

In 2012-13, AANDC's EMA Program base funding totaled $22.2 million, of which approximately $16.5 million was allocated for fire suppression agreements with certain provinces. As of April 1, 2013, the Department has allocated an additional $19.1 million to fund bilateral agreements with provincial emergency management organizations. Incremental funding is sought annually from to fund response and recovery costs related to extreme emergencies (2012-13 - $20 million, 2011-12 - $142 million, and 2010-11 - $28 million).

Audit Objectives and Scope

The objectives of this audit were to provide senior management with assurance on the adequacy and effectiveness of AANDC management controls supporting implementation of the Department's legislative responsibilities for emergency management assistance to First Nations communities; and to assess control processes for administering EMA Program grants and contributions, including compliance with EMA Program authorities and AANDC policy requirements.

The scope of the audit covered the period from April 1, 2011 to December 31, 2012, and included program governance, program design, program implementation, and financial management and controls. While the audit assessed the appropriateness of the design of financial management controls for administering emergency management expenditures claims, only limited testing of the operational effectiveness of these controls was performed in three AANDC regions; accordingly, the audit did not conclude on the operational effectiveness of these transactional controls.

The regional offices in scope were selected based on frequency of emergencies and relative size of historical emergency response and recovery costs. Our audit intended to assess reconciliation processes where an advance payment or reimbursement of expenditures had been initially paid by AANDC and was later determined to be an eligible claim under Public Safety Canada's Disaster Financial Assistance Arrangement (DFAA) Program. We were unable to fully test these reconciliation controls given that Public Safety Canada had not yet completed its processing of claims for emergencies that occurred on-reserve between April 1, 2011 and December 31, 2012 in the three regions visited.

Statement of Conformance

The Audit of Emergency Management Assistance conforms to the Internal Auditing Standards for the Government of Canada, as supported by the results of the quality assurance and improvement program.

Observed Strengths

Supported by an appropriate governance framework and senior management commitment, AANDC is focused on improving the design of the EMA Program. Despite being actively engaged in national emergency management working groups between 2010 and 2012, federal and provincial governments have not reached agreement on a consistent national approach to delivering emergency management programming on-reserve. In response, AANDC is refocusing its attention to bilateral negotiations with each province.

Leading up to and during emergencies impacting First Nations communities, AANDC generally collaborates well with first responders, provincial governments, and host communities for the delivery of emergency response and recovery services.

All four pillars of emergency management (prevention/mitigation; preparedness; response and recovery) were implemented in the regions with a marked emphasis on response and recovery activities. In the absence of provincial agreements and directed approaches from AANDC Headquarters, regions have adopted innovate approaches to delivering preparedness services to First Nation communities.

Conclusion

AANDC senior management provides leadership and assumes overall responsibility and accountability for the EMA Program. Under the authority of the Deputy Minister, the AANDC EMA Program has an appropriate governance framework and clear roles and responsibilities for emergency management.

Broad national objectives have been established for the EMA Program, but insufficient performance information is collected to support effective program design and decision-making. AANDC is building internal capacity to undertake program improvement initiatives in response to the need to refocus efforts onto bilateral negotiations with each province and away from negotiating a multilateral national framework.

A more strategic and comprehensive approach to risk identification would inform AANDC mitigation and preparedness activities. EMA Program preparedness, response and recovery activities were generally effective in most regions, but the Program would benefit from additional guidance and best practice information from the Emergency Issues and Management Directorate of Regional Operations Sector with respect to the thoroughness and completeness of regional emergency management plans, standard operating procedures and after-action reports.

In the absence of bilateral agreements with provinces defining eligible expenses and authorization requirements, regions cannot effectively scrutinize invoices downstream. Regions and provinces need to better define eligible EMA Program expenditures or funding formulae through bilateral agreements to ensure clarity and consistency with Program Terms and Conditions. Finally, the EMA Program Terms and Conditions are ambiguous about the eligibility of capital recovery and mitigation costs and regional staff were unclear about which AANDC authority was being employed to manage such projects.

Recommendations

The audit team identified areas where the EMA program could be strengthened, resulting in three recommendations, as follows:

- The Senior Assistant Deputy Minister, Regional Operations should ensure that the draft EMA Program Performance Measurement Strategy is finalized and that the final version is in alignment with approved program objectives and authorities. The Senior Assistant Deputy Minister should also ensure that a regime of regular monitoring and reporting of program results is implemented.

- The Senior Assistant Deputy Minister, Regional Operations should ensure that a risk-based all-hazards approach to the EMA Program, in accordance with the Emergency Management Act, is adopted.

- The Senior Assistant Deputy Minister, Regional Operations should ensure that the EMA Authority and supporting guidelines are reviewed and updated to promote a consistent understanding of eligible projects and expenditures. To ensure effective emergency management activities across AANDC regional offices, the Senior Assistant Deputy Minister, Regional Operations should ensure that standardized processes are developed and implemented so that expectations, objectives and priorities are clear with respect to emergency management plans, procedures for response activities, and after-action reports as well as the approval of emergency expenditures and the scrutiny of invoices.

1. Background

An Audit of the AANDC Emergency Management Assistance (EMA) Program was included in the 2012-2013 to 2014-2015 Risk-based Audit Plan approved by the Departmental Audit Committee on February 23, 2012. This audit was identified as a departmental priority because the EMA Program is highly sensitive and of increasing importance due to the increase in natural disasters and related costs. Moreover, emergency management programming is very challenging from a funding perspective due to complex funding criteria and the involvement of multiple parties.

The federal government's overall approach to emergency management recognizes the increased potential for various types of catastrophes as a result of accumulating risks associated with such factors as critical infrastructure dependencies and interdependencies, climate change, environmental change, animal and human diseases, the global movement of people, goods and information, and terrorism. Under the leadership of Public Safety Canada, the federal government has given high priority to emergency management in recent years, as evidenced by:

- promulgation of the Emergency Management Act in 2007;

- joint development by federal-provincial-territorial Ministers responsible for emergency management of an Emergency Management Framework for Canada and a National Emergency Response System in 2011; and

- issuance of a Federal Policy for Emergency Management and a Federal Emergency Response Plan in 2011, along with related guidance on emergency management planning and risk assessment.

All of these documents describe Canada's approach to emergency management as characterized by:

- an all-hazards, risk-based approach to address both natural and human-induced emergency situations;

- four interdependent components (prevention/mitigation, preparedness, response and recovery);

- shared responsibilities among federal, provincial and territorial governments and their partners, including individual citizens and communities; and

- recognition that most emergencies in Canada are local in nature and managed by municipalities or at the provincial or territorial level.

AANDC's emergency management assistance to First Nations is not addressed specifically in any of the legislation, policies and plans mentioned above. Rather, the Minister of Aboriginal Affairs and Northern Development has accepted responsibility for providing emergency management support to on-reserve First Nation communities on the basis of:

- the responsibility of all federal Ministers under the 2007 Emergency Management Act …to identify risks that are within or related to their area of responsibility, to develop appropriate emergency management plans in respect of those risks, to maintain, test and implement the plans, and to conduct exercises and training in relation to the plans"; and

- The legislative authority of the Government of Canada for "Indians, and Lands reserved for Indians" under the Constitution Act 1867, an authority that is delegated to the Minister under the Indian Act and the Department of Indian Affairs and Northern Development Act

The Deputy Minister of AANDC issued the National Emergency Management Plan (NEMP) in 2009 and again in 2011 with the stated purpose of providing "…a national framework for the roles and responsibilities of emergency management: mitigation, preparedness, and response and recovery activities in First Nation communities across Canada." The NEMP is comprehensive and aligned with the Emergency Management Act and with direction issued by Public Safety Canada in its role as the lead federal department for emergency management.

In recent years, First Nation communities have been significantly affected by natural disasters, including major floods, forest fires and tornados. This pattern reflects the increased frequency and intensity of emergencies throughout Canada. First Nations communities, however, are often more vulnerable to natural disasters due to their isolation, poor socio-economic conditions, small populations and associated lack of capacity. AANDC has had authority since November 2004 for delivery of emergency management assistance through transfer payment arrangements with First Nations recipients and various levels of government. The Department has exercised its responsibilities by promoting and providing emergency preparedness within First Nations communities, emergency response and evaluation during disasters and remediation of infrastructure and housing after emergencies. AANDC also has specific authority for forest fire suppression activities and provides financial assistance for search and recovery activities based on compassionate grounds.

A February 2010 evaluation report by the AANDC Evaluation, Performance Measurement, and Review Branch confirmed the need for the EMA Program, but concluded that "the current program delivery mechanisms and structure do not provide the required framework to pursue an all hazard approach to emergency management as required under the Emergency Management Act." The report made recommendations in the following three areas: roles and responsibilities, program funding structure and performance measurement. Since the issuance of the report, AANDC has taken steps to respond to these recommendations by bringing clarity to roles and responsibilities for emergency management, developing guidelines to support regional discussions with the provinces for service agreements, and developing a Performance Measurement Strategy.

Within AANDC, the Director of Emergency Issue and Management Directorate (EMD) is responsible for the development, implementation and maintenance of AANDC's NEMP. The Director is situated under the Sector Operations Branch of the Regional Operations Sector and has a complement of nine full time staff working on operations, planning and policy development. In regions, the Regional Director General is responsible for implementation of the EMA Program with the support of full-time Emergency Management Coordinators. There are ten full time employees assigned to regional emergency management activities in AANDC's seven south of 60 regional offices and three part-time coordinators who provide emergency management support in the North for Yukon, North West Territories, and Nunavut.

Regional Emergency Management Coordinators handle all functions normally assigned physical EM operations centres.

During emergency situations, the AANDC Headquarters (HQ) Emergency Management (EM) Operations Centre is responsible for invoking the NEMP, thereby coordinating and monitoring emergency management activities impacting First Nation communities from a national perspective and for responding to queries from senior officials within the Department, including the offices of the Minister and Deputy Minister. The AANDC HQ EM Operations Centre is also responsible for coordinating activities with AANDC Regional EM Operations Centers. The NEMP states that Regional EM Operations Centers should ideally mirror the HQ organization but on a smaller scaled due to limited staff. We noted that the three regions visited did not maintain physical operations center, but rather relied on the regional Emergency Management Coordinators to handle all the functions normally assigned to such a facility.

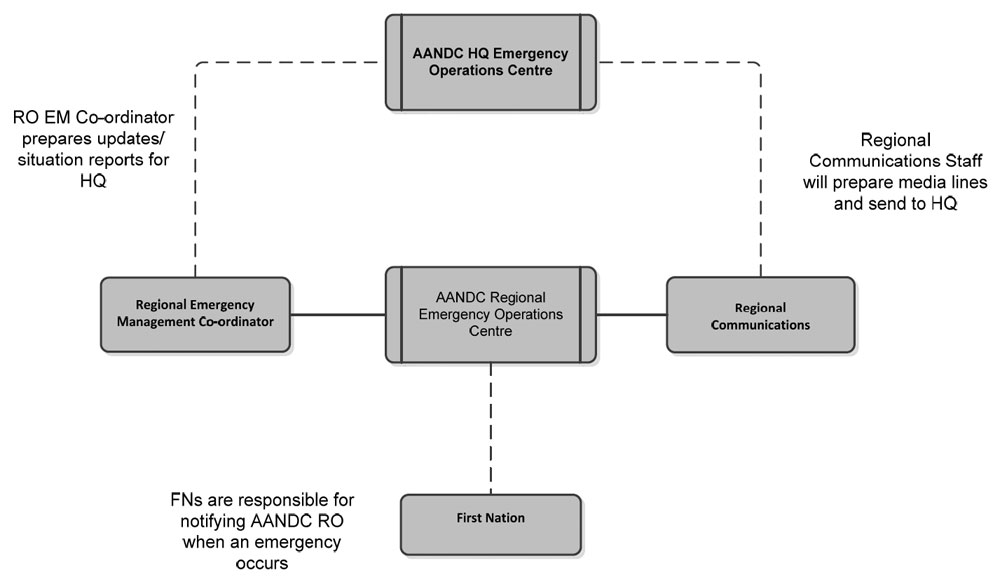

Text alternative for AANDC Regional Governance Structure for Emergency Management

The figure titled "AANDC Regional Governance Structure for Emergency Management" depicts five entities that are involved in emergency management and the types of reporting relationships among them.

First Nations are responsible for notifying AANDC Regional Operations (RO) when an emergency occurs. As such, the First Nation entity is depicted as having a functional reporting relationship (dotted line connection) with their respective AANDC Regional Emergency Operations Centre.

The AANDC Regional Emergency Operations Centre has horizontal reporting relationships with two regional entities: the Regional Emergency Management Co-ordinator, and the Regional Communications function. These two entities, in turn, report functionally (dotted line) to the AANDC Headquarters (HQ) Emergency Operations Centre. That is, the Regional Operations Emergency Management Co-ordinator prepares updates/situation reports for HQ, and Regional Communications staff prepare media lines and send them to HQ.

Despite these limitations, regional Emergency Management Coordinators are effective in discharging their responsibilities, including notifying the AANDC HQ Operations Centre of emergency activities or events and establishing and maintaining reporting relationships with:

- First Nations communities;

- provincial and territorial emergency management organizations;

- Public Safety Canada;

- non-government organizations such as the Red Cross and the Salvation Army;

- private sector representatives;

- Aboriginal organizations;

- volunteer organizations; and

- local governments and municipalities.

In 2012-13, AANDC’s EMA Program base funding totaled $22.2 million, of which approximately $1.9 million was allocated to salaries and operations costs of EMD HQ and regional EMA Programs, $16.5 million was allocated for fire suppression agreements with certain provinces and $3.5 million was available to fund emergency management preparedness, response, recovery and mitigation costs. Incremental funding is sought annually to fund responses and recoveries from extreme emergencies as they occur (e.g. severe flooding, storm surges and wildfire evacuations). EMA Program management have advised the audit team that the Department will be allocating an additional $19.1 million of base funding to the program effective 2013-14 to fund bilateral agreements with provinces, however we were unable to confirm this allocation at the time this report was written.

| Actuals | 2010-11 | 2011-12 | 2012-13 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Atlantic | 4,599,230.00 | 11,764,956.79 | 8,503,506.84 |

| Quebec | 136,514.00 | 133,157.00 | 723,267.00 |

| Ontario | 567,500.00 | 17,951,064.91 | 2,853,510.12 |

| Manitoba | 9,966,720.88 | 75,669,789.00 | 6,950,000.00 |

| Saskatchewan | 8,156,599.54 | 24,781,540.48 | 17,876,108.00 |

| Alberta | 0.00 | 8,882,956.00 | 324,006.00 |

| British Columbia | 878,959.02 | 6,107,175.27 | 2,288,324.21 |

| Yukon | 0.00 | 0.00 | 578,372.00 |

| Northwest Territories | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Nunavut | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Total | 24,305,523.44 | 145,290,639.45 | 40,097,094.17 |

| Actuals | 2010-11 | 2011-12 | 2012-13 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Prevention / Mitigation | 1,556,755.00 | 1,131,358.00 | 841,000.00 |

| Preparedness | 4,713,376.69 | 19,508,116.40 | 6,403,948.07 |

| Response | 12,997,313.16 | 95,480,615.05 | 18,394,292.28 |

| Recovery | 4,801,186.40 | 29,050,660.00 | 14,447,768.82 |

| Search and Recovery | 236,892.19 | 119,890.00 | 10,085.00 |

| Total | 24,305,523.44 | 145,290,639.45 | 40,097,094.17 |

2. Audit Objectives and Scope

2.1 Audit Objectives

The objectives of this audit were to provide senior management with assurance on the adequacy and effectiveness of AANDC management controls supporting implementation of the Department’s legislative responsibilities for emergency management assistance to First Nations communities; and to assess control processes for administering EMA Program grants and contributions, including compliance with EMA Program authorities and AANDC policy requirements.

2.2 Audit Scope

The scope of the audit covered the period from April 1, 2011 to December 31, 2012 and focused on AANDC’s capacity to deliver the EMA Program in conformance with applicable legislation, including the Emergency Management Act (2007), the Indian Act (1985), and the Department of Indian Affairs and Northern Development Act (1985). Audit findings are arranged under the following four broad program areas:

- EMA Program Governance;

- EMA Program Design;

- EMA Program Implementation; and

- Financial Management and Controls.

Audit criteria were drawn from applicable legislation, as well as from the AANDC National Emergency Management Plan (2009), An Emergency Management Framework for Canada (Second Edition, January 2011), the Federal Policy on Emergency Management (2011), the Federal Emergency Response Plan (2011), the Emergency Management Planning Guide issued by Public Safety Canada, and Program Authority #330 (Contributions for Emergency Management Assistance for Activities on Reserve). Audit criteria were also drawn from Canadian best practices for emergency management, including the Canadian Standards Association Standard Z1600 – Emergency Management and Business Continuity Programs. A detailed listing of criteria is provided in Appendix A.

3. Approach and Methodology

The audit of the EMA Program was planned and conducted in accordance with the Internal Auditing Standards for the Government of Canada as set out in the Treasury Board Policy on Internal Audit.

Sufficient and appropriate audit procedures have been conducted and evidence gathered to support the audit conclusions provided and contained in this report.

During the planning phase, program related documents were reviewed and preliminary interviews were conducted with EMA Program officials, and a selection of regional management and staff with EM responsibilities to gain an understanding of the Program. A regional questionnaire was developed and completed by eight of AANDC’s regional offices to obtain additional information and data on the regional implementation of the EMA Program. Finally, a risk assessment was conducted to identify and assess the most significant risks to the EMA Program, and for each of the highest risks, the audit team identified expected mitigating controls and possible control gaps.

Audit criteria were developed to cover areas of highest risk. The criteria served as the basis for developing the detailed audit program for the conduct phase of the audit.

The principal audit techniques employed included:

- interviews with key individuals with responsibility for the EMA Program at HQ and a selection of regional offices;

- analysis and evaluation of EMA Program documentation in EMD and in a selection of regional offices related to areas of program planning, program design, program costing, program implementation, reporting, financial management, and operating procedures and guidelines; and,

- examination of AANDC actions before, during and following a selected emergency situations in First Nations communities, including review of operational responses and administration of financial transactions in three AANDC regions (Ontario, Saskatchewan and Atlantic).

4. Conclusions

AANDC senior management provides leadership and assumes overall responsibility and accountability for the EMA Program. Under the authority of the Deputy Minister, the AANDC EMA Program has an appropriate governance framework and clear roles and responsibilities of emergency management.

Broad national objectives have been established for the EMA Program, but insufficient performance information is collected to support effective program design and decision-making. AANDC is building internal capacity to undertake program improvement initiatives in response to the need to refocus efforts onto bilateral negotiations with each province and away from negotiating a multilateral national framework.

A more strategic and comprehensive approach to risk identification would inform AANDC mitigation and preparedness activities. EMA Program preparedness, response and recovery activities in regions were generally effective in most regions, but the Program would benefit from additional guidance and best practice information from EMD with respect to the thoroughness and completeness of regional EM plans, standard operating procedures and after-action reports.

In the absence of bilateral agreements with provinces defining eligible expenses and authorization requirements, regions cannot effectively scrutinize invoices downstream. Regions and provinces need to better define eligible EMA Program expenditures or funding formulae through bilateral agreements to ensure clarity and consistency with Program Terms and Conditions. Finally, the EMA Program Terms and Conditions are ambiguous about the eligibility of capital recovery and mitigation costs and regional staff were unclear about which AANDC authority(ies) was being employed to manage such projects.

5. Findings and Recommendations

5.1 PROGRAM GOVERNANCE

5.1.1 Legislative Responsibilities of the Minister

The Minister of Aboriginal Affairs and Northern Development has delegated authority for emergency management under the Indian Act and the Department of Indian Affairs and Northern Development Act

In Canada, the provinces and territories are responsible for emergency management within their respective jurisdictions; however, the Constitution Act 1867 prescribed the legislative authority of the Government of Canada for "Indians, and Lands reserved for the Indians." This authority is delegated to the Minister of Aboriginal Affairs and Northern Development under the Indian Act and the Department of Indian Affairs and Northern Development Act.

All federal Ministers are responsible under the 2007 Emergency Management Act "to identify risks that are within or related to their area of responsibility, to develop appropriate emergency management plans in respect of those risks, to maintain, test and implement the plans, and to conduct exercises and training in relation to the plans."Footnote 2 The Minister of Aboriginal Affairs and Northern Development has accepted responsibility for supporting on-reserve First Nation communities in the four pillars of emergency management: mitigation/prevention, preparedness, response and recovery.

5.1.2 Senior Management Engagement

AANDC senior management provides leadership and assumes overall responsibility and accountability for the EMA Program.

The Deputy Minister issued the NEMP in 2009 and again in 2011, with the stated purpose of providing "a national framework for the roles and responsibilities of emergency management: mitigation, preparedness, and response and recovery activities in First Nation communities across Canada."

We found that the Deputy Minister volunteered to have the AANDC Emergency Management Plan evaluated by Public Safety Canada (PSC) in 2011, evidencing his interest in ensuring that an appropriate plan was in place and in line with federal government expectations. More recently, AANDC senior managers have been engaged in reviewing the EMA Program to improve its effectiveness across all four pillars of emergency management, to ensure its long-term sustainability, and to develop guiding principles to support negotiations for comprehensive bilateral emergency management service agreements with the provinces.

Interviews with AANDC senior managers at headquarters and in the regions visited highlighted that they are knowledgeable and actively engaged in the EMA Program, and that they understand the importance of strong relationships with First Nations, provinces, and other partners and stakeholders, including other federal departments such as Health Canada and PSC. AANDC senior managers participate actively in interdepartmental emergency management committees at the Deputy Minister, Assistant Deputy Minister and Director General levels, as well as in the Senior Officials Responsible for Emergency Management (SOREM) forum and the SOREM Aboriginal Emergency Management Working Group, which include participants from AANDC, PSC, the provinces and territories.

5.1.3 The National Emergency Management Plan

The AANDC NEMP establishes governance and management arrangements and provides a comprehensive national framework for the department's EMA Program.

The NEMP is comprehensive and aligned with the Emergency Management Act and with direction issued by Public Safety Canada in its role as the federal lead department for emergency management.

The NEMP sets out an AANDC emergency management governance structure that is consistent with the Federal Emergency Response Plan and that builds on existing internal and interdepartmental governance arrangements. The audit found that Regional Emergency Management Plans replicated the governance and management structures set out in the NEMP, but were inconsistent regarding region-specific information and timely updates.

When the NEMP was first issued in 2009, AANDC committed to undertake a full review of the document at least every three years. The Deputy Minister reissued the NEMPin 2011, providing greater precision to the Minister's responsibility for supporting on-reserve First Nation communities in the four pillars of emergency management.

5.2 PROGRAM DESIGN

5.2.1 Overall Program Objectives

AANDC has established broad national objectives for the National Emergency Management Plan:

- protect the health and safety of First Nation communities and individuals;

- meet AANDC's obligations under the Emergency Management Act;

- protect property and infrastructure, First Nations lands, assets, and the environment;

- mitigate the risks of emergencies in First Nation communities through proactive measures;

- ensure a coordinated national approach to emergency management in First Nations communities;

- enhance the capacity of First Nation communities to effectively address emergency situations;

- reduce economic and social losses for First Nations communities; and

- provide guidance for AANDC's emergency management planning and operations in the North.

5.2.2 Program Review and Improvement

AANDC is building internal capacity to undertake program improvement initiatives in response to the need to refocus efforts on establishing bilateral negotiations with each province.

AANDC has reviewed the EMA Program several times in recent years, including a program evaluation in 2009-2010, a performance review focused on the 2011-2012 Manitoba floods, and other assurance activities focused on the administration of program funds. EMD is responding to these reviews by clarifying EMA Program roles and responsibilities, seeking more stable program funding, and developing a performance measurement strategy.

Significant program review work is now under way, including development of options to improve the emergency management response regime for First Nations, collaboration with PSC on a First Nations component for a proposed national disaster mitigation program, and the assessment of long-term funding options to support comprehensive bilateral emergency management service agreements with provincial governments.

We learned that, through the SOREM Aboriginal Emergency Management Working Group, AANDC focused its efforts between July 2010 and December 2012 on negotiating a common national framework through a multilateral process involving all provinces, territories and other federal stakeholders. More recently, the Department has refocused its attention to bilateral negotiations with provinces in light of the multilateral decision not to pursue national overarching principles through the SOREM Aboriginal Emergency Management Working Group. While the department has undertaken program redesign work to define the future success of AANDC‘s emergency management activities for First Nations on reserve, additional efforts are required in negotiating service agreements with provinces, developing an all-hazards risk assessment, implementing mitigation and prevention programming, and enhancing training and exercises.

5.2.3 Performance Measurement

The EMA Program collects insufficient performance information to support program design and management decisions. Work is underway to update the EMA Program Performance Measurement Strategy.

In response to an evaluation of the EMA Program in 2009-2010, EMD initiated work on a Performance Measurement Strategy to assess the program's relevance and performance, and to support planning decisions. The draft 2012-2013 to 2017-2018 version of the Performance Measurement Strategy addresses all four pillars of emergency management and includes five key performance indicators. EMD managers continue to adapt and refine the Performance Measurement Strategy to reflect ongoing progress.

At the time of the audit, AANDC had one performance indicator, the "percentage of First Nation communities with an emergency management plan." We found no documented record of achievement of this performance measure, either in quarterly performance reports or the Departmental Performance Report. While this indicator provides useful information it does not support assessments of the quality of emergency preparedness activities or performance of the other three pillars of the EMA Program. The Audit did find that management establishes annual operational priorities for the program and tracks results against targets on a quarterly basis.

Recommendation:

1. The Senior Assistant Deputy Minister, Regional Operations should ensure that the draft EMA Program Performance Measurement Strategy is finalized and that the final version is in alignment with approved program objectives and authorities. The Senior Assistant Deputy Minister should also ensure that a regime of regular monitoring and reporting of program results is implemented.

5.3 PROGRAM IMPLEMENTATION

5.3.1 Headquarters Program Implementation

EMD provides effective communication and coordination support to regional staff during emergencies but provides limited support to regions in support of the delivery of emergency mitigation and preparedness activities.

EMD effectively provides regional emergency management managers and staff with coordination and communication support during emergencies. For example, the HQ EM Operations Centre coordinates and monitors emergency management activities impacting First Nation communities from a national perspective and serves as a hub for the flow of emergency-related information to and from HQ and regional offices.

We found that EMD has established annual operational priorities through the departmental business planning and quarterly reporting processes. While these plans effectively establish near term tasks and targets for headquarters-level activities, they include limited consideration of implementation of the EMA Program in regions.

Despite active engagement through national emergency management working groups, federal and provincial governments have not agreed on a nationally consistent approach to deliver EMA Programming on reserve.

A working group established under the intergovernmental SOREM forum and the SOREM Aboriginal Emergency Management Working Group chaired by the Director of EMD and co-chaired by the Director, Public Safety Initiatives, Alberta Emergency Management Agency, commenced work in 2009 on a national framework for the establishment of emergency management agreements between AANDC and provincial governments. During the audit, we were advised by PSC and AANDC officials that the SOREM working groups decided in late 2012 to refocus their activities away from a nationally consistent framework towards a statement of principles document to guide federal-provincial negotiations. In response to this decision to suspend work on a national framework; EMD responded by drafting principles to guide regions in their negotiations with the provinces. This initiative is part of the Department's broader review of the EMA Program and an essential step in supporting regions in negotiations with the respective provinces.

AANDC has not completed an all-hazards risk assessment to support its mitigation and preparedness activities.

Under the 2007 Emergency Management Act, all federal Ministers are responsible for identifying "risks that are within or related to their area of responsibility,"Footnote 3 as the basis for preparing, maintaining, testing and implementing emergency management plans in respect of those risks. Public Safety Canada issued methodology guidelines in 2011-2012 to assist federal government institutions "in fulfilling their legislative responsibility to conduct mandate-specific risk assessments as the basis for EM planning."Footnote 4

We found that most AANDC risk identification and assessment activities under the EMA Program are short-term, and tend to focus on upcoming floods, fires and other recurring natural disasters. AANDC maintains "community profiles" that identify the critical infrastructure of communities which are prone to floods, their capacity and whether they have emergency plans in place and firefighting capability.

The Department does not regularly conduct medium to long-term all-hazards risk assessments for First Nation communities at the national level nor were regional risk assessments developed in the three regions visited during audit fieldwork. The audit team learned that Public Safety Canada is exploring the possibility of developing a national all-hazards risk registry with information that could be relevant to the risks facing Canada's First Nations communities.

A more strategic and comprehensive approach to risk identification and assessment (combining AANDC, PSC, provincial and First Nations efforts) would help inform AANDC mitigation and preparedness activities, support departmental funding requests, raise awareness of the potential impact of emergencies beyond natural disasters, and inform short-, medium- and long-term planning, including for types of emergencies that have not occurred or that might increase in frequency and severity in future.

Recommendation:

2. The Senior Assistant Deputy Minister, Regional Operations should ensure that a risk-based all-hazards approach to the EMA Program, in accordance with the Emergency Management Act, is adopted.

5.3.2 Regional Program Implementation

Emergency management is a shared responsibility in Canada, starting with individual citizens who are expected to prepare for disasters and to contribute to the resilience of their communities. Provincial and territorial governments have responsibility within their respective jurisdictions, while the federal government exercises leadership at the national level and in relation to Federal Reserve lands and other exclusive fields of jurisdiction.

AANDC depends on provincial governments for the delivery of emergency response and recovery services. While only four provinces have agreements, all provinces visited during the audit have assumed responsibility for response.

Emergency management programming at AANDC is designed on the principle that the Department will negotiate agreements with the provinces to respond to emergencies in First Nation communities in exchange for reimbursement of eligible expenditures. The purpose of these collaborative agreements is to ensure that First Nation communities "have access to comparable emergency assistance services available to other non-aboriginal communities in their respective provinces."Footnote 5

At the time of the audit, AANDC had agreements in place with Alberta and Saskatchewan, while letters and Memoranda of Understanding had been established with British Columbia and Nova Scotia. Through interviews with regional program managers we found that provinces without formal, written agreements with AANDC have nevertheless provided the department with verbal assurance that they will respond to emergencies in First Nations communities. The province of Manitoba is a notable exception because the provincial government has deemed emergency management support to First Nation communities an exclusively federal responsibility.

Regions have developed regional Emergency Management Plans, with varying levels of region-specific direction and guidance.

According to the NEMP, AANDC regions are responsible for developing, exercising, implementing and maintaining Regional Emergency Management Plans. We found inconsistency among the plans in the three regions visited, including in the level of detail and clarity with respect to region-specific roles and responsibilities, concepts of operations, and linkages to other stakeholders, including provincial emergency management organizations. In two regions, the regional plans mimicked the NEMP and included only limited region-specific information. The other regional plan was comprehensive and addressed emergency operations processes, links to provincial emergency social and health services, environmental forecasts, and provided guidance on the provincial disaster relief program. This plan also included annexes with regional reporting templates and First Nations community risk inventories. This approach is a best practice which should be shared with other AANDC regions.

In collaboration with their provincial counterparts, AANDC regional staff responds effectively to emergencies affecting First Nations communities.

According to the NEMP, the responsibility for identifying and initiating a response to an emergency rests with the local First Nations community and the appropriate provincial emergency management organization, while the role of AANDC (when necessary) is to "provide logistics coordination support in response to a provincial request", including providing "linkages to other departments and various suppliers so the requested resources are provided to the designated emergency hazard area."

We examined in detail how AANDC regions responded to a variety of specific emergencies in First Nation communities since April 2011. In every case, we found that regional staff members worked capably and effectively and in close collaboration with other partners. The work of regional staff in the response phase was often more robust and complex than the NEMP description, in some cases because of the lack of an agreement with the province. For example, in one province, a regional employee negotiated service and funding agreements with municipal-level communities identified by the province as potential "hosts" for evacuated First Nations residents, and other regional employees were deployed as liaison officers to these host communities. In this capacity, they served as liaison between the evacuees and the responding organizations, provided translation services if required, kept AANDC senior management updated, and pre-approved expenditures. In another region, the Emergency Management Coordinator was responsible for assisting First Nations with financial support, the identification of technical resources and engineering and construction firms and the availability of heavy equipment.

In all responses examined, we found that AANDC regional EMA staff and communications staff collaborated on providing regular situation reports to senior AANDC officials and to the Headquarters EM Operations Centre, First Nation communities, provincial and territorial emergency management organizations, PSC, non-government and local governments and municipalities.

Standard operating procedures for responding to emergency situations vary in thoroughness and completeness from region to region.

Standard operating procedures are important tools for achieving a uniform emergency response by employees across an organization. The audit found that not all AANDC regions have standard operating procedures and that those in place varied considerably.

In one Region, a Senior Officer's Desk Book provided explicit direction on provincial emergency management procedures, contacts, local emergency plans, links to emergency social services, environmental forecasts, templates for reporting to senior management, and guidelines for eligible costs. A second region had a handbook that included emergency contact lists, phone and fax numbers, evacuation service standards and guidelines, and templates for recording daily evacuation event, while a third region's standard operating procedures were limited to EMD templates for issuing notifications on emergency incidents.

While the audit found that post-emergency after-action reports were completed for a majority of emergencies reviewed, these documents did not always include AANDC-specific lessons learned, and recommendations were not always followed through.

After-action reports are an important tool for AANDC to learn from their own and others' experiences, successes and failures in managing emergencies. The NEMP establishes expectations of when and how regions are to prepare after-action reports and provide them to EMD.

In the regions we visited, we found no consistency in the regional approaches to the preparation of after-action reports, or in how progress on opportunities was tracked for improvement for the regions visited. Some regional Emergency Management Coordinators advised the audit team that responsibility for drafting after-action reports lies with the First Nations affected by emergency situation or with the provinces. The lack of standardized after-action reports can impede efforts to improve stakeholder relations and EMA programming at both regional and national levels.

Recommendation:

See recommendation #3.

5.3.3 Four Pillars of Emergency Management

Emergency Management planning should be based on all four pillar of emergency management. We found that emergency management plans in all regions visited covered the four pillars: prevention/mitigation; preparedness; response and recovery. The amount of programming attention and funding directed to each component varied from region to region and from year to year, depending on such factors as the frequency of emergencies affecting First Nation communities, the extent of recovery activities under way, and variations in A-base funding for mitigation and preparedness work.

5.3.3.1 Prevention and Mitigation

While mitigation figures prominently in the NEMP, AANDC investments in prevention/mitigation projects are limited and linked to recent emergencies.

The overarching mission of the NEMP is to "help to mitigate or reduce the impact of emergencies on the safety, health and security of affected First Nations individuals and property." More specifically, the NEMP assigns responsibility to AANDC regions to work with First Nation communities and provincial emergency management organizations to "take steps to mitigate potential emergencies (e.g. flood dykes, risk based construction of capital projects build out of harm's way, flood berms)."

In interviews, senior AANDC officials observed that investments in carefully selected mitigation projects could yield significant long-term cost savings by reducing the costs of repeatedly responding to and recovering from annual events, such as floods and fires. However, during the audit we did not find an AANDC or PSC led cost benefit analysis to assess investments in emergency prevention and mitigation activities on reserve. Several officials referred to the building of the Red River Basin Floodway as the most prominent example, citing estimated savings of $6 billion on a $60 million investment from the 1960s.

The 2009-2010 evaluation of the EMA Program recommended that AANDC identify appropriate resources in alignment with its roles and responsibilities and, more specifically, that the Department ensures it has the ability to provide mitigation services in accordance with departmental obligations under the Emergency Management Act.

AANDC provides limited investments in capital projects during recovery to prevent or mitigate potential future disasters.

The 2011 Emergency Management Framework for Canada (signed by federal-provincial-territorial Ministers responsible for emergency management) points to the strong relationship between long-term sustainable recovery and prevention and mitigation of future disasters: "Forward-looking recovery measures allow communities not only to recover from recent disaster events, but also to build back better in order to help overcome past vulnerabilities."

The audit team learned of some investments in mitigation, but these were limited and linked to the recovery phase following recent emergencies. One capital project successfully mitigated the damage from storm surges by building 10-foot-high sea walls along a river shoreline. The sea walls have proven to be effective in protecting these communities from flooding during subsequent events. Other projects improved resistance to extreme flooding. Notwithstanding these examples, we found that AANDC does not consistently assess information about the physical, economic and social benefits of not simply returning a First Nation community to its former state, but rather increasing the community's resilience against future disasters.

We found little evidence that AANDC had identified and prepared estimates of resources required to fund its mitigation responsibilities. During the course of the audit we were advised that EMD is developing an enhanced mitigation component for its emergency management program. As a part of the enhancements, a manager from the Community Infrastructure Branch has been tasked with developing a cost-benefit analysis approach to inform investments and to ensure that capital projects include consideration of emergency management mitigation risks.

At the same time, AANDC is working collaboratively with PSC in support of the development of a First Nations component as part of a proposed national disaster mitigation program that would allocate funding for both structural and non-structural mitigation activities aimed at reducing risks.

5.3.3.2 Preparedness

In the absence of provincial agreements, direction from AANDC Headquarters and dedicated funding for supporting First Nation preparedness, some regions have adopted innovative approaches to delivering preparedness services to First Nation communities.

Preparedness includes actions taken to be ready to respond to a disaster and manage its consequences through measures taken prior to an event, for example, emergency response plans, mutual assistance agreements, resource inventories and training, equipment and exercise programs.

One of the eight objectives of the NEMP is to "enhance the capacity of First Nation communities to effectively address emergency situations." In the regions visited, we found that investments in preparedness were aligned to this objective. For example, one region has contracted with an aboriginal corporation specializing in the delivery of technical services to First Nation communities to provide support for preparedness activities. Under this contract, the corporation assists communities in identifying and assessing relevant risks and hazards, developing and testing emergency management plans, and providing training to community members. As a result, approximately 60 per cent of First Nation communities in that province now have emergency management plans in place, a significant increase from approximately 20 per cent before the contract was put in place 4 years earlier.

We found that AANDC regions generally did not receive copies of First Nations emergency management plans and therefore were not in a position to comment on their currency, quality or attention to all significant hazards and risks.

At least one region includes information about First Nations emergency plans in the community profiles maintained by AANDC for each First Nations community. In other regions, these profiles have no emergency management content (for example, on the community's emergency management capacity and planning, on emergencies affecting the community in recent years, or on funding provided to the community by AANDC under each of the four pillars of emergency management.).

One region is partnering with Health Canada to develop all-hazards emergency management plans for First Nations in their region, starting with six communities. This initiative stemmed from earlier AANDC-Health Canada collaboration on pandemic planning and business continuity planning.

5.3.3.3 Response

AANDC regions have collaborated effectively with most provincial emergency management organizations to coordinate and manage responses to emergencies affecting First Nation communities.

The response pillar of emergency management consists of actions taken during or immediately before or after a disaster to manage its consequences through, for example, emergency public communication, search and rescue, emergency medical assistance and evacuation to minimize suffering and losses associated with disasters.

We found that, even in the absence of formal agreements, AANDC regions rely on provincial emergency management organizations (EMOs) to assume the lead role during an emergency response period and to have plans, procedures and resources in place to support First Nation communities. Across Canada, provincial EMOs generally coordinate the response activities of all government /non-governmental organizations, provide seats for their partners in their 24/7 emergency operations centers, compile comprehensive situation reports, and handle media relations. These arrangements generally work well in the case of emergencies in First Nation communities, with AANDC regional staff working in tandem with provincial (EMO) colleagues and aligning their activities and processes with those of the province.

AANDC regions generally respond capably and effectively to emergency situations.

As indicated in section 5.3.2 of this report, the audit examined in detail how AANDC regions responded to a variety of specific emergencies in First Nation communities since April 2011. In every case, we found that regional staff members worked capably and effectively and in close collaboration with other partners.

We noted, however, that some aspects of the AANDC emergency management coordination structure as set out in the NEMP were not activated during emergency responses, and that regions implemented other aspects in ways that suited local circumstances. For example, according to the NEMP, the Director of EMD may escalate or de-escalate among three response levels (Level 1: routine activities; Level 2: partial augmentation of Headquarters and relevant Regional EM operations centers and key staff; Level 3: extensive augmentation of both operations centers and staff). We found no evidence that EMD applied this response level system to any of the emergencies examined during the audit.

The NEMP also indicates that AANDC Regional EM Operations Centers "should ideally mirror" the Headquarters Emergency Management Operations Centre (EMOC), "but on a smaller scale due to limited staff." The audit found that the three regions visited do not maintain physical operations centers, but rather rely on the regional Emergency Management Coordinator to handle all the functions normally assigned to such a facility.

5.3.3.4 Recovery

The 2011 Emergency Management Framework for Canada defines recovery as actions taken to repair or restore conditions to an acceptable level through measures taken after a disaster, for example, return of evacuees, trauma counseling, reconstruction, economic impact studies and financial assistance. The NEMP identifies returning a First Nations community "to a state of normalcy which existed prior to the emergency" as a priority and further states that recovery focuses on "the repatriation or restoration of conditions to an acceptable level." Similarly, EMA Program Authority defines recovery as "the remediation of the community, their infrastructure and houses to the pre-existing condition as rapidly as possible." However, the EMA Program Authority is silent on the potential to prevent or mitigate future disasters by the choices taken during the recovery phase.

The audit found that regional approaches to recovery activities varied, with some provinces leading some or all recovery activities and other provinces leaving these activities to AANDC. Where AANDC regions led recovery projects, we generally found that projects were being managed by staff responsible for managing capital infrastructure projects. While we did not assess enough transactions to conclude on the effectiveness of these controls, we did find that they are appropriate for managing recovery projects.

5.4 FINANCIAL MANAGEMENT AND CONTROLS

5.4.1 Administering Recipient Funding Agreements

The EMA Program Terms and Conditions (EMA Program Ts&Cs), approved in November 2004, first came into effect in April 2005. The EMA Program Ts&Cs were last updated and approved by the Minister in February 2013 to increase the maximum amount payable to any one recipient from $5 million to $10 million. The EMA Program's Ts&Cs describe the program objectives as well as the types of activities and expenditures which can be funded through contribution agreements. We completed an analysis of the current and prior EMA Program Ts&Cs and found that they are ambiguous about what types of projects and expenditures can be funded under this authority. More specifically, they are internally inconsistent about whether capital recovery and mitigations projects may be funded.

Section 5 of the EMA Program Ts&Cs describe "Eligible Initiatives and Projects" as virtually any emergency mitigation, preparedness, response or recovery project, while Section 6,"Type and Nature of Eligible Expenditure", makes it clear that mitigation and recovery expenditures of a capital nature are specifically not eligible. Departmental officials confirmed that capital projects are funded through the Capital Facilities and Maintenance Program which provides for these types of projects, despite financial transactions being coded to the EMA Program account codes. Our analysis of the evolution of the EMA Program Ts&Cs between 2004 and 2013 indicates that the defining of eligible projects and initiatives occurred in 2010 when all AANDC program terms and conditions were redrafted to conform to changes to the Policy on Transfer Payments.

The EMA Program Authority is ambiguous about whether capital projects for recovery and mitigation are eligible.

Given that emergency management recovery projects of a capital nature have been consistently approved, capital reconstruction projects appear to be in keeping with their intended use of the funds. Accordingly, we have concluded that the Department was within its authorities to fund capital related projects administered by First Nations and provinces through its approved Program Ts&Cs for Capital Facilities and Maintenance and that such spending is most likely in line with the intended use of funds. However, we found that financial coding and reporting controls were inadequate for tracking EMA Program transactions that were administered under the Capital Facilities and Maintenance program authority (i.e. these costs were coded to the EMA Program in the financial system and reports and not tracked against the CFM program authority).

Our audit affirmed the need for all regions to better define eligible EMA Program expenditures or funding formulae through bilateral agreements with provinces and to ensure consistency with EMA Program Ts&Cs and Capital Facilities and Maintenance Ts&Cs.

In the absence of bilateral agreements with provinces defining eligible expenses and authorization requirements, regions cannot effectively scrutinize invoices downstream.

While we did not perform in-depth testing of transfer payment files, we did assess a small sample of funding agreements and corresponding invoices and payments to determine whether regions had designed appropriate financial management control processes for administering EMA Program contribution agreements. The audit found that AANDC's regional processes varied considerably and that this approach was necessary considering that provincial approaches to the delivery of emergency management differ from province to province. In most regions there is no clear understanding with provinces about what types of expenditures will be reimbursed by AANDC and whether pre-authorization is required for some or all types of expenditures. Notwithstanding the existence of ambiguity in what is and is not eligible, we found that some regions exercised greater scrutiny than others in reviewing invoices and reconciling claims. For example two regions in the scope of the audit principally relied upon provincial or municipal authorities to ensure that all claims were valid and supported by invoices. The other two regions reported that they reviewed invoices and claims in depth and sought clarification from recipients as required.

Our audit intended to assess reconciliation processes for situations where an advance payment or reimbursement of expenditures had been initially paid by AANDC and it was later determined to be an eligible claim under Public Safety Canada's DFAA Program. We were unable to test these reconciliation controls given that there were no such transactions in our scope period for the three regions visited (i.e. Public Safety Canada was two to five years in arrears in processing transactions so any such reconciliations had not yet occurred). Through interviews with regional financial staff, the audit found that approaches varied across regions for handling claims that may be eligible under the Public Safety Canada DFAA Program. One region had agreed with Public Safety Canada that AANDC would pay for the costs of certain emergencies, but treatment of other emergencies in the province remained unclear.

Recommendation:

3. The Senior Assistant Deputy Minister, Regional Operations should ensure that the EMA Authority and supporting guidelines are reviewed and updated to promote a consistent understanding of eligible projects and expenditures. To ensure effective emergency management activities across AANDC regional offices, the Senior Assistant Deputy Minister, Regional Operations should ensure that standardized processes are developed and implemented so that expectations, objectives and priorities are clear with respect to emergency management plans, procedures for response activities, and after-action reports as well as the approval of emergency expenditures and the scrutiny of invoices.

6. Management Action Plan

| Recommendations | Response / Actions | Responsible Manager (Title) | Planned Implementation Date |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. The Senior Assistant Deputy Minister, Regional Operations should ensure that the draft EMA Program erformance Measurement Strategy is finalized and that the final version is in alignment with approved program objectives and authorities. The Senior Assistant Deputy Minister should also ensure that a regime of regular monitoring and reporting of program results is implemented. | A PMS for EMAP is currently being drafted and will align with program objectives and authorities. | Director General, Sector Operations | 2013-2014 Q2 |

| Once the PMS is finalized, EMD will ensure that a regime of regular monitoring and reporting of program results is implemented. | 2014-2015 and ongoing | ||

| 2. The Senior Assistant Deputy Minister, Regional Operations should ensure that a risk-based all-hazards approach to the EMA Program, in accordance with the Emergency Management Act, is adopted. | Sector Operations (SO) will conduct medium- and long-term all-hazards risk assessments for First Nations and use the results to inform AANDC’s emergency management program activities. This will involve steps such as:

|

Director General, Sector Operations | Completing risk assessment: 2014-2015 Incorporating results into decision making: 2015-2016 |

| 3. The Senior Assistant Deputy Minister, Regional Operations should ensure that the EMA Authority and supporting guidelines are reviewed and updated to promote a consistent understanding of eligible projects and expenditures. To ensure effective emergency management activities across AANDC regional offices, the Senior Assistant Deputy Minister, Regional Operations should ensure that standardized processes are developed and implemented so that expectations, objectives and priorities are clear with respect to emergency management plans, procedures for response activities, and after-action reports as well as the approval of emergency expenditures and the scrutiny of invoices. | EMD will address these issues through reviewing EMAP terms and conditions and updating them where necessary. EMAP will also review AANDC’s regional emergency management plans and update them where necessary. EMD, in conjunction with regional offices, will negotiate bilateral arrangements with the provinces which will include approaches to emergency management plans, response activities, after action reports as well as spending and accountability provisions. |

Director General, Sector Operations | Review EMAP terms and conditions:

2013-2014 Q3 Regional emergency management plans: 2013-2014 Q4 Negotiation of bilateral arrangements: 2014-2015 |

Appendix A: Audit Criteria

| Audit Criteria and Controls | References (Acronyms provided following the table) |

|---|---|

| 1. AANDC’S EMA Program is in place, with appropriate and clearly defined objectives, roles, responsibilities and accountabilities. | EMA 6.(1), (2) FPEM 7 CSA Z1600-4 |

1.1. AANDC’s EMA Program complies with all applicable federal legislation, plans and policies. |

EMA 6.(1), (2) FPEM 7 CSA Z1600-4.1, 5 |

1.2. AANDC has internal structures to provide governance for its emergency management activities and to ensure consistency and interoperability with government-wide emergency management governance structures. |

EMA 6.(1), (2) FPEM 7 CSA Z1600-4.1, 5 |

1.3. AANDC establishes program objectives and performance measures for the EMA Program. |

EMA 6. (1), (2) FPEM 7.8. CSA Z1600-4.4.3 |

1.4. AANDC establishes clear roles and responsibilities for the EMA Program. |

EMA 6.(1), (2) FPEM 7 CSA Z1600-4 |

| 2. AANDC’s senior management supports the EMA Program actively and appropriately. | EMA 6. (1), (2) FPEM 5, 7 TBA 300 4, 5, 6 CSA Z1600-4.1 |

2.1. AANDC senior management provides leadership and assumes overall responsibility and accountability for the EMA Program. |

EMA 6.(1), (2) FPEM 7 CSA Z1600-4.1 |

2.2. AANDC senior management has reviewed and approved the EMA Program objectives and plan. |

EMA 6.(1), (2) FPEM , 7 CSA Z1600-4.4.7 |

2.3. AANDC conducts a periodic management review of the EMA Program, based on the goals, objectives and evaluation of the program. Management assesses appropriateness of resources and opportunities for continuous improvement of the program. |

EMA 6.(1), (2) FPEM 7 CSA Z1600–8.1 |

| 3. AANDC establishes program-level plans to guide delivery of the EMA Program. | EMA 6.(1), (2) FPEM 7 CSA Z1600 5.1 |

3.1. AANDC has performed thorough analysis of trends in the nature, frequency and severity of emergencies, including analysis of corresponding response costs, to inform its plans. |

EMA 6. (1) (2) NEMP 1.5 CSAZ1600 5.1.1 |

3.2. AANDC established a program-level plan for the EMA program which addresses significant risks and conforms to requirements of the Emergency Management Act and Public Safety Canada guidance. |

EMA 6.(1), (2) FPEM 7 CSA Z1600 -5.1.2 |

| 4. AANDC has procedures and arrangements in place to support the delivery of provincially comparable emergency management assistance services to all First Nation communities. | EMA 6.(1), (2) FPEM 7 CSA Z1600-6.3 |

4.1. AANDC enters into collaborative agreements with provincial governments to ensure that First Nation communities have access to emergency assistance services that are comparable to those available to provincial residents. |

EMA 6.(1), (2) FPEM 7 CSA Z1600-6.3 |

4.2. AANDC EMA plans and procedures include direct links to collaborative agreements with provinces and other stakeholders. |

EMA 6.(1) (2) FPEM 7 CSA Z1600-6.3.2 |

4.3. AANDC participates in emergency management training and exercises within the Department, the Regions, and with other emergency response organizations. |

EMA 6.(1) (2) FPEM 7.12 CSA Z1600 6.2.2 |

| 5. AANDC’s budget for the EMA Program is aligned to program objectives, plans and priorities. | EMA 6. (1), (2) NEMP 4, 5, CSAZ1600 A.4.4.5 |

5.1. AANDC’s EMA Program funding allocations are aligned to program plans and areas of risk. |

EMA 6.(1), (2) FPEM 7 CSA Z1600 6.2.2 |

5.2. AANDC has developed a fully-costed estimate of the EMA Program to accompany its funding request(s). |

EMA 6. (1), (2) NEMP 4 CSAZ1600 A.4.4.5 |

5.3. AANDC performs analysis of historical EMA Program costs and trends in the nature, frequency and severity of emergencies to support its budget estimates and forecasts. |

EMA 6. (1), (2) NEMP 4, 5, CSAZ1600 A.4.4.5 |

| 6. AANDC has a risk-based approach to its EMA Program for First Nation communities, and has an up-to-date and comprehensive risk assessment. | EMA 6 (1), (2) EMFC p. 7 NEMP 1.6 CSA Z1600-6 |

6.1. AANDC systematically identifies and assesses risks related to the provision of emergency management assistance to First Nation communities, including consideration of all hazards, historical trends, anticipated changes in the risk environment, and potential impacts. |

EMA 6 (1), (2) FPEM. 7 NEMP 1.6 CSA Z1600-6.1.2 |

| 7. AANDC has developed procedures and controls to support First Nation communities before, during and after emergency situations. | EMA 6. (1), (2) TBA 300 9, 10, 11, 12 CSA Z1600-4., 6 |

7.1. AANDC mitigation strategies are risk-based and take into account program constraints, operational experience and cost-benefit analysis. |

EMA 6 (1), (2) FPEM. 7 EMFC p. 7 CSA Z1600-6.1.3 |

7.2. AANDC’s capital infrastructure programming supports the objective of mitigating emergency management-related risks in First Nation communities. |

EMA 6 (1), (2) FPEM. 7 EMFC p. 7 CSA Z1600-6.1.3.2 |

7.3. AANDC has established a recovery strategy, including financial compensation, for the recovery of functions, services, resources, facilities, programs and infrastructure. |

EMA 6.(1), (2) EMPC p. 8. TBA 300 6, 11, 12 CSAZ1600- 4.6 |

7.4. AANDC Regions support First Nation communities First Nation communities in developing and implementing robust emergency management plans and capacity to respond to most likely emergency scenarios (e.g. plans, arrangements, emergency equipment, evacuation, water, shelter, etc.) |

EMA 6. (1), (2) FPEM 7 CSA Z1600-4.4 |

| 8. AANDC has financial management controls in place to manage the EMA Program in accordance with financial requirements and authorities. | EMA 6. (1), (2) TBA 300 6, 11, 12 CSA Z1600-4.6 |

8.1. AANDC has policies and directives in place for expediting financial decisions in accordance with established authorization levels and fiscal policies. |

EMA 6. (1), (2) TBA 300 6, 11 12 NEMP 4 CSA Z1600-4.6 |

8.2. AANDC demonstrates to decision-makers that it has implemented program funding criteria and controls to ensure that funds are managed prudently and consistently, and where applicable, in alignment with provincial standards. |

EMA 6. (1), (2) NEMP 4 TBA 300 12 CSAZ1600-4.6.2, 4.6.3 |

8.3. AANDC’s EMA Program includes appropriate activities, approaches and funding to ensure that First Nation communities most vulnerable to emergencies have the capacity to prepare for, respond to and recover from emergencies. |

EMA 6 (1), (2) FPEM. 7 EMFC p. 7 CSAZ1600-4.6.2, 4.6.3 |

8.4. AANDC has controls in place to verify expenditures (occurrence and eligibility) and to recover unspent or ineligible funds. |

EMA 6. (1), (2) TBA 300 6, 11.12 NEMP 4 CSAZ1600-4.6.2, 4.6.3 |

Acronyms

| EMA: |

Emergency Management Act, 2007 |

|---|---|

| IA: |

Indian Act, 1985 |

| DIANDA: |

Department of Indian Affairs and Northern Development Act, 1985 |

| FERP: |

Federal Emergency Response Plan, 2011 |

| EMFC |

Emergency Management Framework for Canada, 2007 |

| FPEM: |

Federal Policy for Emergency Management, 2009 |

| NEMP: |

Aboriginal Affairs and Northern Development Canada's National Emergency Management Plan |

Acronyms related to Canadian Standards Association Standard on Emergency Management Programs:

CSA Z1600 – 4: Program Management

CSA Z1600 – 5: Planning

CSA Z1600 – 6: Implementation

CSA Z1600 – 7: Exercises, Evaluations and Corrective Actions

CSA Z1600 – 8: Management Review