Archived - Evaluation of the Implementation of the First Nations Fiscal and Statistical Management Act

Archived information

This Web page has been archived on the Web. Archived information is provided for reference, research or record keeping purposes. It is not subject to the Government of Canada Web Standards and has not been altered or updated since it was archived. Please contact us to request a format other than those available.

Date: April 2011

Project Number: 10014

PDF Version (445 Kb, 82 Pages)

Table of Contents

- List of Acronyms

- Executive Summary

- Management Response and Action Plan

- Letter in response to the report from the First Nations Statistical Institute

- 1. Introduction

- 2. The Evaluation

- 3. Findings - Relevance and Performance

- 4. Findings - First Nations Tax Commission

- 5. Findings - First Nations Financial Management Board

- 6. Findings - First Nations Finance Authority

- 7. Findings - First Nations Statistical Institute

- 8. Findings - Efficiency and Economy

- 9. Conclusions and Recommendations

- Appendix A - Key Findings by Evaluation Question

- Appendix B - Profiles of the Four FSMA Institutions

- Appendix C - FSMA Logic Model

List of Acronyms

Executive Summary

This is the final report of the evaluation of the implementation of the First Nations Fiscal and Statistical Management Act (FSMA or the Act). In line with Treasury Board requirements, this evaluation assesses the relevance and performance of the implementation of FSMA and provides a review of the provisions and operations of FSMA. It was conducted to inform the renewal of authorities and to support a legislative review of the Act, which is scheduled to be conducted by Indian and Northern Affairs Canada's (INAC) Governance Branch in fiscal year 2011-12. This evaluation includes the following authorities:

- Grant to the First Nations Finance Authority pursuant to the FSMA;

- Contributions to First Nations Institutions for the Purpose of Enhancing Good Governance;

- Grant to support the establishment of a $10M credit enhancement fund for the enhancement of the First Nations Finance Authority's credit rating; and

- Payment to the First Nations Statistical Institution for operating expenditures.

FSMA affirms First Nations powers to raise local revenues through property taxation and to access more favourable interest rates through pooled investment and borrowing. To access these powers, a First Nation must request, through Order in Council, to be scheduled under the Act and develop the required laws and management systems. The Act creates four institutions to oversee the regime and to support First Nations who are exercising powers under the Act: the First Nations Tax Commission (FNTC), the First Nations Financial Management Board (FMB), the First Nations Finance Authority (FNFA), and the First Nations Statistical Institute (FNSI).

The Institutions Unit of the Professional and Institutional Development Directorate, Governance Branch, Regional Operations, is responsible for managing INAC's support of the implementation of FSMA, which includes:

- Managing grants and contributions in support of the implementation of the Act;

- Managing Governor in Council processes for the purpose of appointing FNSI, FMB and FNTC Commission/Board members and adding First Nations to the schedule;

- Managing regulatory processes;

- Conducting the legislative review and facilitating amendments to the Act; and

- Facilitating interaction between the institutions for matters such as regulation development.

The evaluation focuses on the period from the date the Act came into force (April 2006) to March 2011, and includes a case study on each of the four institutions, key informant interviews with departmental officials, a review of program files and documents, and a review of published literature. Two notable limitations of the methodology were that INAC's expectations in terms of operationalization and achievement of outcomes were not well defined and limited participation by First Nation communities in the evaluation. To address the first issue, the evaluation team adopted a working definition of operational that included: the establishment of required governance structures, the use of financial resources, and the extent to which each institution is delivering services in its mandated areas.

The evidence supports the conclusion that the FSMA addresses a continued need by providing a choice to First Nations wishing to improve capacity and to have access to financing tools used by local governments to advance economic development. It alsoaddresses longstanding issues related to the timeliness and completeness of Aboriginal statistics. This is relevant and aligns with federal government priorities, particularly those related to Aboriginal governance capacity and economic development in Aboriginal communities. Moreover, the provisions and operations of the FSMA, including the mandates of its four institutions, continue to be relevant to INAC's strategic outcomes for the Government.

The design of the FSMA is appropriate and is largely being delivered as intended. However, each institution has shown varying degrees of implementation:

- FNTC's mandate under the FSMA is relevant to facilitating third-party investment in reserve property by increasing the transparency and fairness of the tax regime. FNTC is essential to property tax regimes on reserve as it is responsible for administering Section 83 of the Indian Act as well as FSMA part 2. The evaluation found that the FNTC is fully operational and is implementing its responsibilities under FSMA as intended. First Nations have generated, through FNTC, over $170M in local revenue ($70M of which is under FSMA and $100M under s.83).

- FMB 's mandate under the FSMA is essential for the issuance of a bond by the FNFA as the FMB is responsible for certifying the financial health of First Nation. FMB also addresses the need for intervention to remedy situations where a First Nation is improperly or unfairly applying local revenue laws (upon request by FNTC) or has not met payment obligations to FNFA (upon request by FNFA). FMB has experienced some delays in implementation, but is now implementing its responsibilities under the FSMA as intended. Twenty-six First Nations are developing the required financial administration law and management systems to become FMB certified.

- FNFA's mandate under the FSMA is relevant in that it provides First Nations with access to affordable financing for infrastructure and economic development. Demand for the FNFA's services is expected to increase once the first bond has been issued.FNFA is implementing its responsibilities under the FSMA as intended, however, the establishment of the governance structure required under the Act and the achievements of intended outcomes related to financing depend on the issuance of the first bond. FNFA is currently offering investment advice and services, which have resulted in roughly $1.5M earnings for the 38 First Nations investment members.

- There continues to be a need for reliable and current financial statistics to support the FSMA pooled financing model and First Nations' policy and planning needs. However, delays in implementation may have impacted the relevancy of the FNSI mandate under the FSMA as other organizations are beginning to address these needs. FNSI is now becoming operational and is currently undertaking an environmental scan to identify specific areas where FNSI can provide statistical services and has developed an 'Ethical Policy on the Protection of Data and Information', an essential industry best practice for collecting First Nations statistics. The evaluation also found evidence that FNSI recently began delivering products to clients by updating a data inventory and nine community profiles.

The evidence also concludes that the institutions have formalized their relationships and are working together to support First Nations who choose to access the Act.

As identified at the onset of the evaluation, it was difficult to assess the overall impacts of FSMA due to the status of implementation of each institution as well as the lack of performance measurement in place for FSMA. However, as discussed above, there are signs of progress for all four institutions and evidence of community level impacts for FNTC, FMB and FNFA. Areas for improvements in efficiency were identified and include: the development of a performance measurement strategy; a review of the structure of the authorities supporting the implementation of the Act; the coordination of institutions; and the alignment with other INAC initiatives such as economic development and infrastructure programming, self-government activities, as well as other optional legislation.

Based on the findings of the evaluation, it is recommended that:

- INAC's Chief Financial Officer reviews and recommends any potential changes necessary to rationalize the dedicated FSMA spending authorities (and other related authorities) and to reinforce linkages with other relevant initiatives, including, for example, economic development.

- Given the current operational status of the FSMA institutions, INAC re-examines the expected results of INAC's support and the funding required to achieve those expected results. Also, INAC works with First Nations institutions to develop performance measurement strategies and reporting regimes in line with Treasury Board and INAC standards, particularly with respect to roles and responsibilities, risks, targets, time lines, reporting burden and a strategy for measuring impacts on First Nation communities.

- As part of the legislative review, INAC ensures that an assessment of the mandate of the FNSI is undertaken that considers the results of the environmental scan and the corporate plan vis-à-vis respecting its activities. The review should also include an assessment of progress being made towards the issuance of a bond.

- INAC strengthens coordination with other related INAC initiatives, including other "opt-in" initiatives, self-government (including the British Columbia Treaty process), economic development and infrastructure programming, to ensure that the FSMA regime is being utilized to its maximum potential.

Management Response and Action Plan

Project Title: Evaluation of the Implementation of the First Nations Fiscal and Statistical Management Act (FSMA)

Project #: 10014

1. Management Response

The Evaluation of the Implementation of the First Nations Fiscal and Statistical Management Act (the Evaluation) is the first of a series of projects aimed at the review and/or evaluation of the FSMA and the four Institutions created by it. The work completed in this Evaluation will feed into the seven-year legislative review of the First Nations Fiscal and Statistical Management Act (FSMA) and Institutions, which will be tabled in both Houses of Parliament before March 23, 2012.

The Regional Operations Sector has had the opportunity to review the findings of the Evaluation in consultation with the partner FSMA Institutions. Because each Institution has shown varying degrees of implementation since the coming into force of the Act, assessing the overall impacts of the initiative proved to be difficult. Nevertheless, several areas shone through in the Evaluation and recommendations which will shape the Regional Operations Sector and Institutions' way forward, including the finalization of Performance Measurement and Risk Management strategies. Action items listed in the attached chart are the result of discussions both internally and with the FSMA Institutions, and are seen as appropriate measures to take in light of the four specific recommendations resulting from the Evaluation.

2. Action Plan

| Recommendations | Actions | Responsible Manager (Title / Sector) |

Planned Start and Completion Dates |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. That the Chief Financial Officer review the potential, and recommend any changes necessary, to rationalize the dedicated FSMA spending authorities (and other related authorities) and to reinforce linkages with other relevant initiatives including, for example, economic development. | We concur. | Chief Financial Officer / Chief Financial Officer Sector | Start Date: |

| The potential for rationalizing the spending authorities that support the implementation of the First Nations Fiscal and Statistical Management Act will be undertaken in the larger context of INAC authority rationalization. This review will also examine the potential to reinforce linkages with other initiatives and include collaboration with other sectors. | Completion: | ||

| 2. Given the current operational status of the FSMA institutions that INAC re-examine the expected results of INAC's support and the funding required to achieve those expected results. Also work with First Nations Institutions to develop performance measurement strategies and reporting regimes in line with Treasury Board and INAC standards, particularly with respect to roles and responsibilities, risks, targets, time lines, reporting burden and a strategy for measuring impacts on First Nation communities. | We concur | Director General /Regional Operations Sector | Start Date: 2006 and ongoing |

| Work has begun on a mandated legislative review and the re-examination of expectations for INAC support and funding requirements will be included in this review before being tabled to each house of Parliament. | Completion: March 23, 2012 | ||

| A Performance Measurement Strategy is being developed for the FSMA with its' institutions. The Strategy will consider reporting burden on recipients and include measuring impacts of the FSMA on First Nations communities. Although it was initially scheduled to be complete in 2011-12, Regional Operations Sector will postpone its completion until 2012-2013 to ensure the inclusion of any regulatory and/or legislative changes resulting from the Legislative Review. | March 31, 2013 | ||

| A Risk Assessment was initiated in 2011-2012 and is currently being conducted with the Institutions, with the support and advice of Audit and Evaluation Sector, to assess the risks associated with the FSMA and its Institutions. | September 30, 2012 | ||

| The FSMA Institutions currently report against the requirements of the legislation, Treasury Board authorities and respective funding agreements. | Ongoing | ||

| Reporting Burdens will be assessed according to the Reducing Reporting Burden exercise being led by the Deputy Minister's Special Representative on Reduced Reporting. | March 31, 2012 | ||

| 3. As part of the legislative review, that INAC ensure that an assessment of the mandate of the FNSI is undertaken that considers the results of the environmental scan and the corporate plan vis-à-vis respecting its activities. The review should also include an assessment of progress being made towards the issuance of a bond. | We concur. | Director General / Regional Operations Sector |

Start Date: In progress |

| As part of the Legislative Review, the Regional Operations Sector and the First Nations Statistical Institute (FNSI) will ensure that an assessment of its mandate is undertaken that takes into account the plans and priorities identified as a result of the 2010 Environmental Scan and its Corporate Plan for the period 2011-2014. The Terms of Reference for the Legislative Review will include a process for the assessment of progress being made towards the issuance of a bond under the FSMA. |

Completion: March 23, 2012 |

||

| 4. That INAC strengthen coordination with other related INAC initiatives, including other "opt-in" initiatives, self-government, economic development and infrastructure programming, to ensure the FSMA regime is being utilized to its maximum potential. | We concur | Director General/Regional Operations Sector | Start Date: September 2011 |

| The Regional Operations Sector will use existing government structures such as Director General Implementation and Operations Committee and Director General Policy Committee to promote synergies between departmental stakeholders. | Completion: Ongoing |

||

| The Regional Operations Sector is exploring the possibility of drafting a Framework for the inclusion of self-governing First Nations in the FSMA with the FSMA Institutions. | December 31, 2011 | ||

| The Lands and Economic Development Sector regularly participates in FSMA meetings and information sharing with the Community Infrastructure Branch will further enhance coordination of infrastructure programming. | Ongoing | ||

| The Regional Operations Sector is currently conducting an analysis of overlapping requirements in opt-in legislation within INAC. | September 30, 2011 |

I recommend this Management Response and Action Plan for approval by the Evaluation, Performance Measurement and Review Committee

Original signed on April 18, 2011 by:

Name: Judith Moe

Position: A/ Director, Evaluation, Performance Measurement and Review Branch

I approve the above Management Response and Action Plan

Original signed on April 18, 2011 by:

Name: Gina Wilson

Position: Sr. Assistant Deputy Minister

Regional Operations Sector

I approve the above Management Response and Action Plan

Original signed on April 18, 2011 by:

Name: Susan MacGowan

Position: Chief Financial Officer

The Management Response / Action Plan for the Evaluation of the Implementation of the First Nations Fiscal and Statistical Management Act were approved by the Evaluation, Performance Measurement and Review Committee on April 19, 2011.

Letter in response to the report from the First Nations Statistical Institute

PDF Version (76 Kb, 4 Pages)

November 9, 2011

Anne Scotton

Chief Audit and Evaluation Executive

Aboriginal Affairs and Northern Development Canada

Audit and Evaluation Sector

10 Wellington St

Gatineau QC

K1A 0H4

Dear Ms. Scotton,

On behalf of my colleagues at the First Nations Statistical Institute (FNSI) I am writing to present our views on the Draft Final Report titled Evaluation of the Implementation of the First Nations Fiscal and Statistical Management Act (FSMA). While more detailed comments were made on earlier drafts of the report, we felt it important to provide an overall response to the evaluation's main findings and conclusions.

As the report states, the evaluation was conducted to support the legislative review of the Act. It must, therefore, provide a fair and accurate picture of the Act's implementation.

Let me start by saying that we agree with the evaluation's main conclusions:

- The FSMA addresses a continued need by providing a choice to First Nations wishing to improve capacity and access to financing tools to advance economic development, and responds to longstanding issues related to the timelines and completeness of Aboriginal statistics.

- The provisions and operations of the FSMA, including the mandates of its four institutions, continue to be relevant to Indian and Northern Affairs Canada's (INAC, now Aboriginal Affairs and Northern Development Canada) strategic outcomes for the Government.

- The design of FSMA is appropriate and is largely being delivered as intended.

- The four institutions have formalized their relationships and are working together to support First Nations who choose to access the Act.

We also accept the evaluation's finding that FNSI has experienced protracted start-up phase. As the evaluation notes:

- It was created without the benefit of an existing organization on which to build.

- Delays in the Governor in Council appointment process – while common in Crown corporations – were particularly significant for FNSI. It took 32 months to establish the FNSI Board. Without a Board, key operational decisions and directions could not be made.

- While some interim funding was provided by INAC, Ministerial and Treasury Board approval of the Corporate Plan was required before FNSI could access its full appropriation.

However, we believe that the evaluation understates the progress that has been made in making FNSI operational.

- During 2010-11, FNSI consolidated its organizational capacity by developing and implementing a wide range of, financial and informational management, technology and human resources policies and procedures. Office space was secured and recruitment began for key staff. A performance measurement strategy and associated evaluation plan were developed.

- FNSI established a data stewardship policy that forms the basis for the future partnerships with First Nations on data collection, use and reporting.

- FNSI completed a comprehensive assessment of client needs that included federal departments and agencies, provincial and territorial bureau statistics, First Nations and Aboriginal communities, governments and organizations, to understand the role that statistics play in their work, data needs and gaps, and expectations regarding how FNSI can assist. This Environmental Scan was a key input to the development of FNSI's program agenda.

- FNSI delivered statistical products in the form of an updated data inventory and nine community assessments of the impacts of resource development. A Memorandum of Understanding with Statistics Canada was in the final stages of approval to formalize working relationships and areas of collaboration. Discussions were also underway with INAC and the Assembly of First Nations on the development of similar MOUs.

- The 2011-12 to 2015-16 Corporate Plan was approved by the FNSI Board and was being finalized in consultation with INAC, Treasury Board Secretariat and the Office of the Auditor General.

We disagree with the assertion that delays in implementation may have impacted the relevancy of the FNSI mandate under the FSMA as other organizations are beginning to address these needs.

- There is little direct evidence presented in the evaluation to support this assertion.

- To date, discussions that the First Nations Financial Management Board and the First Nations Finance Authority have had with credit agencies have not required data or analysis from FNSI. FNSI is prepared to support its sister organizations as and when required.

- While FNSI has a broad mandate, it is not intended to be the sole provider of statistical information on First Nations. Other organizations have their own resources, priorities and work plans. FNSI works with them to identify gaps and areas of collaboration and to avoid duplication. For example, FNSI has an agreement in place with INAC to launch, host and maintain the Community Well-Being Index on the FNSI website.

We appreciate the difficulty of evaluating what might be best described as a moving target. The evaluation was undertaken over January to March 2011 at a time when FNSI was making the transition to becoming fully operational. And as the report recognizes, the evaluators were limited by the lack of a clear definition of what was required for an institution to be considered operational, and by the small number of documents and interviews that served as the basis for the FNSI case study.

We believe that FNSI is now well-positioned to work with its partners to deliver the statistical products and services to support its clients and stakeholders.

I would be pleased to discuss these comments with you should you wish. I am also taking the liberty of forwarding a copy of this document to Brenda Kustra, Director General, Governance Branch, Aboriginal Affairs and Northern Development Canada as input to the report on the legislative review.

Sincerely,

Keith Conn

Chief Operating Officer

C.c.

Brenda Kustra, Director General, Governance Branch, Aboriginal Affairs and Northern Development Canada

Deanna Hamilton, President, First Nations Finance Authority

Harold Calla, President, First Nations Financial Management Board

Ken Scopick, Chief Operating Officer, First Nations Tax Commission

1. Introduction

1.1 Overview

This is the final report of the Evaluation of the Implementation of the First Nations Fiscal and Statistical Management Act (FSMA or the Act). The evaluation was conducted to meet Treasury Board requirements, to inform the renewal of authorities, and to support a legislative review of the Act, which is scheduled to be conducted by Indian and Northern Affairs Canada's (INAC) Governance Branch in fiscal year 2011-12. This legislative review, including the findings of this evaluation, is to be submitted by the Minister, via INAC Regional Operations, to both Houses of Parliament by March 23, 2012, along with any proposed changes recommended by the Minister.

The evaluation includes a review of the provisions and operations of the Act and covers the time period from when the Act came into force on April 1, 2006, to March 2011. In line with Treasury Board's Policy on Evaluation, the study focuses on relevance and performance (effectiveness, efficiency and economy), and it also examines questions related to design and delivery.

The evaluation was undertaken by the Evaluation, Performance Measurement and Review Branch (EPMRB) of INAC with the assistance of three consulting firms. T.K. Gussman Associates Inc., along with EPMRB officials, conducted the majority of research, analysis and report preparation. BBMD Consulting Inc. provided additional support for a comparative analysis of First Nation communities, and Delsys Research Inc. provided an external peer review and advice on creating linkages between the evaluation and the upcoming legislative review. The evaluation was also supported by an Advisory Committee comprised of INAC officials and representatives of the four FSMA institutions.

The remainder of this introductory section provides an overview of FSMA and its four institutions, as well as an overview of INAC's support for the implementation of the Act. Section 2 of this report presents the evaluation methodology, including an overview of roles and responsibilities for the study. Findings on the relevance and performance of the Act as a whole can be found in Section 3. Sections 4 to 7 present findings for each institution. In Section 8, the report returns to the overall implementation of the Act by presenting the findings on issues related to efficiency and economy. Conclusions and recommendations can be found in Section 9.

Appendices to this report include a crosswalk between the evaluation's questions and conclusions (Appendix A), profiles of the four FSMA institutions (Appendix B), and the overarching logic model for FSMA (Appendix C).

1.2 Profile of the FSMA

1.2.1 The First Nations Fiscal and Statistical Management Act

Governments use their infrastructure and services to stimulate their economy through industrial, commercial, and residential development in their jurisdictions. First Nation communities have faced sizeable challenges in meeting similar local community needs in large part because there is no formal framework under the Indian Act to support the functions of comptrollership, compliance, taxation, standard setting, and access to reliable and relevant information and data that would facilitate First Nation governments in gaining affordable access to capital markets.

Beginning in the late 1980s, First Nations have led a number of initiatives to address these challenges, including:

- In 1988, Bill C-115 amended the Indian Act to provide First Nations with the ability to exercise their jurisdiction over real property taxation on reserve. [Note 1] The Indian Taxation Advisory Board was created to assist in the exercise of that jurisdiction. The amendment to the Indian Act envisaged a statute-based successor to this Board.

- In 1995, the First Nations Finance Authority (FNFA) was incorporated as a limited company for the purposes of issuing debentures using real property tax revenues and providing investment opportunities.

- In 1999, First Nations and the Government of Canada agreed to jointly pursue the benefits of establishing statutory institutions as part of a comprehensive fiscal and statistical management system. [Note 2] At this point, a Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) was signed between INAC and the Assembly of First Nations to work on this legislative project through a National Table on Fiscal Relations. However, according to evaluation participants, by 2001, the Assembly of First Nations' began to distance itself from the legislation and did not support it when it was introduced in the House of Commons.

- In January 2002, two First Nation advisory panels were established to provide expert advice, along with the existing Indian Taxation Advisory Board and FNFA, on the development of fiscal legislation.

- In December 2002, the FSMA was introduced in the House of Commons.

- On March 23, 2005, the legislation received Royal Assent following restatements or reintroductions with amendments over two successive parliaments

- On April 1, 2006, FSMA came into force.

FSMA affirms First Nations fiscal powers to raise local revenues through property taxation and to access more favourable interest rates through pooled investment and borrowing. To access these powers, a First Nation must request, through Order in Council, to be scheduled under the Act and develop the required laws and management systems. The Act creates four institutions to oversee the regime and to support First Nations who are exercising powers under the Act: the First Nations Tax Commission (FNTC), the First Nations Financial Management Board (FMB), the FNFA and the First Nations Statistical Institute (FNSI).

1.2.2 The FSMA Institutions

First Nations Tax Commission: FNTC's purpose is to assist First Nations in building and maintaining efficient property tax regimes and to ensure communities and taxpayers receive the maximum benefit from those systems. FNTC regulates the property tax system by reviewing and approving a First Nation's local revenue laws. It also acts as an administrative tribunal that can review First Nations compliance with the Act and Regulations and interpret the application of those laws and order a remedy if they have been improperly or unfairly applied.

First Nations Financial Management Board: The purpose of FMB is to provide tools and services to support First Nations' fiscal stewardship and accountability and develop capacity to meet their expanding fiscal and financial management requirements. Such capacity is needed to support First Nation economic and community development. FMB provides four key functions in the FSMA borrowing process: Financial Administration Law Standards and approval, Financial Management System Standards and Certification, Financial Performance Standards and Certification, and oversight and intervention services. It also provides intervention services to support the FSMA property tax regime.

First Nations Finance Authority: FNFA's purpose is to help Aboriginal communities build their own infrastructure and economies on their own terms through access to financing and investment services. FNFA assists First Nations in accessing capital markets by creating and managing a pooled investment fund and issuing securities to capital markets to raise revenue for the purpose of lending to borrowing members. To become a borrowing member, a First Nation must have a FMB certificate and unutilized borrowing room.

First Nations Statistical Institute: FNSI's purpose is to provide relevant and reliable statistics, support the promotion of First Nations' economic development and strengthen their statistical capacity. FNSI assists First Nations and the other FSMA institutions by providing statistical information on, and analysis of, the fiscal, economic and social conditions of Aboriginal people and non-Aboriginal people who reside on reserve lands. It is worth noting that FNSI's mandate is broader than supporting FSMA and, therefore, a First Nation does not need to be scheduled under the Act to access its services.

1.2.3 Relations between the Institutions and with First Nations

The Act not only affirms First Nations fiscal powers to collect property tax and access pooled borrowing, but it also creates an integrated system of oversight whereby, the institutions mutually re-enforce each others mandates to ensure the integrity of the system. For example, Section 76 (2) requires a First Nation to possess a FMB certificate to become a borrowing member. Similarly, for the FNFA to issue a long-term loan, a First Nation must have a FNTC approved borrowing law and the loan is to be paid out of property tax revenues (Section 79 (a)(b)). In the event that a First Nation does not meet its payment obligations or improperly/unfairly applies its property tax laws, FMB may require the First Nation to enter into a co-management arrangement (under Section 52 (1)) or a third-party management arrangement (under Section 53 (1)). While collecting First Nation data on a one-time basis satisfies the FMB 's criteria to certify a community for lending, credit agencies require regular updates of community-specific information on an ongoing basis, a role which FNSI assumes.

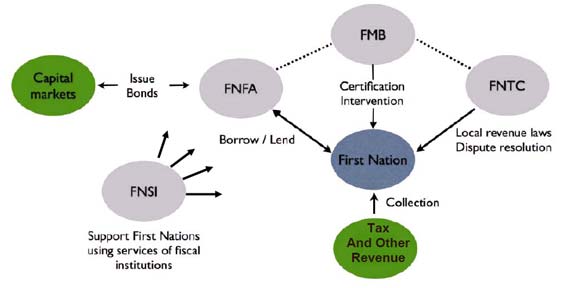

The relationship among participating First Nations, taxpayers on reserve lands, other revenue sources, the fiscal institutions established by the FSMA and capital markets is depicted below:

Figure 1: Relations between the FSMA Institutions and Stakeholders

Source: Adapted from the 2010/11 FMB Corporate Plan.

Figure 1 presents a diagram that shows the connection between a First Nation, tax revenues and capital markets. For example, to collect taxes a First Nation must have an FNTC approved local revenue law and an FMB certification. To access capital markets they must also be a borrowing member of FNFA, who issues bonds to the capital markets. FNSI supports the First Nations and the Institutions by providing relevant statistics.

1.3 INAC's Support for Implementation

1.3.1 Objectives and Expected Outcomes

The FSMA is one of a number of recent optional initiatives supported by INAC, which transfer control of various portions of the Indian Act to First Nations through legislative means. [Note 3] The goal of INAC's support for the implementation of FSMA is to enhance First Nation governance capacity in support of improved economic development and well-being in First Nation communities. As such, INAC recognizes the FSMA institutions as components of a comprehensive and coordinated strategy to strengthen economic development and First Nation accountability to their members and others.

The intermediate outcomes of FSMA are identified in funding documents as:

- greater confidence by First Nation members, taxpayers, investors and other interested parties in First Nation financial management systems;

- increased transparency in property taxation processes;

- increased First Nation capacity in fiscal practices;

- improved data and information sources; and

- increased economic activity on reserve.

1.3.2 Key INAC Actors: Minister, Governance Branch and Legal Services

The relationship between Canada and the governing boards of the FMB, FNTC and FNSI is at the ministerial level and is prescribed in the Act. The relationship between Canada and these three institutions is apparent by virtue of two considerations: their governance structures are appointed through his Excellency the Governor in Council and their corporate plans must be approved by the Minister. As such, the protocols for dealing with the institutions are through the Minister or the Minister's office, with the Department having more direct interaction with the institutions' administrations. FNFA's governing board is elected by its borrowing members; however, much like FMB and FNTC, it receives funding support from INAC and as such, it also has a working relationship between the Department and its administration.

The Institutions Unit of the Professional and Institutional Development Directorate (PIDD), Governance Branch, Regional Operations, is responsible for managing the Department's support of the implementation of the FSMA, as follows:

- Managing grants and contributions in support of implementing the Act.

- Execution of due diligence on work plans and funding agreements

- Negotiation of funding levels for contributions to project-based activities

- Developing a Performance Measurement Strategy to monitor the achievement of the intended outcomes (To date, this includes a draft Results-based Management and Accountability Framework (RMAF) (2006) and a component Performance Measurement Strategy for the Credit Enhancement Fund (2011))

- Reporting on progress through INAC's Quarterly Reports and the Departmental Performance Report

- Execution of due diligence on work plans and funding agreements

- Managing Governor in Council (GIC) processes for the purpose of appointing FNSI, FMB and FNTC Commission/Board members and adding First Nations to the schedule.

- Managing regulatory processes, which to date has involved:

- Financing Secured by Other Revenues Regulations (anticipated to be in force by summer 2011); and

- Adaptation regulations for self-governing First Nations.

- Financing Secured by Other Revenues Regulations (anticipated to be in force by summer 2011); and

- Conducting the legislative review and facilitating amendments to the Act.

- Facilitating interaction between the institutions for matters such as regulation development.

1.3.3 Financial Resources and Authorities

Planned expenditures for the period 2006/07 to 2010/11 were estimated by INAC to be at $74.7M (see Table 1), not including INAC salaries, operation and maintenance. Supporting authorities [Note 4] included:

- Grant to the First Nations Finance Authority pursuant to the First Nations Fiscal and Statistical Management Act;

- Grant to the First Nation Finance Authority for the purpose of enhancing the Authority's credit rating;

- Contribution to First Nations Institutions for the purpose of enhancing good governance; and

- Payment to the First Nations Statistical Institution for operating expenditures.

| Expenditures | 2006-2007 | 2007-2008 | 2008-2009 | 2009-2010 | 2010-2011 | Five Year Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| INAC O&M/salary | unknown | unknown | unknown | unknown | unknown | unknown |

| FNTC | $2,975 | $5,343 | $5,343 | $4,500 | $4,510 | $21,818 |

| FMB | $2,147 | $4,238 | $3,660 | $3,760 | $3,890 | $17,695 |

| FNFA | $1,150 | $850 | $500 | $500 | $500 | $3,500 |

| Credit Enhancement Fund - FNFA* |

- | - | - | - | $10,000 | $10,000 |

| FNSI | $2,841 | $4,888 | $4,300 | $4,700 | $5,000 | $21,729 |

| Total | $9,113 | $15,319 | $12,950 | $13,460 | $13,900 | $74,742* |

Source: Abridged detailed costing from funding documents, including the Credit Enhancement Fund.

*note: the Credit Enhancement Fund is a one-time transfer of $10M to enhance FNFA's credit rating. The capital of the Credit Enhancement Fund may be used to temporally offset any shortfalls in the debt reserve fund (i.e., it will not be spent on FNFA operations).

1.3.4 Performance Measurement and Reporting

A draft RMAF was developed to support INAC's support for the FSMA's implementation in 2006.

FMB and FNTC are required to submit annual corporate plans and annual reports (including performance data) to the Minister for approval (s.118 and s.130, respectively). FNFA is required under s.88 to submit an annual report on operations and a financial statement to the Minister each year. INAC's funding agreements with FNTC, FMB and FNFA also require each institution to implement their corporate plan and submit the required annual report.

Under Section 134 of the Financial Administration Act, the Auditor General of Canada is responsible for auditing FNSI's financial statements. FNSI must publish its audited financial statements 90 days after fiscal year end and present these statements as part of an Annual Report tabled at the organization's Annual General Meeting.

2. The Evaluation

2.1 Purpose and Scope

In line with Treasury Board requirements, this evaluation assesses the relevance and performance of the implementation of FSMA and provides a review of the provisions and operations of FSMA.

This evaluation includes the following authorities:

- Grant to the First Nations Finance Authority pursuant to the FSMA.

- Contributions to First Nations Institutions for the Purpose of Enhancing Good Governance.

- Grant to support the establishment of a $10M credit enhancement fund for the enhancement of the First Nations Finance Authority's credit rating (hereafter 'Credit Enhancement Grant').

- Payment to the First Nations Statistical Institution for operating expenditures.

The evaluation focuses on the period from the date the Act came into force (April 2006) to March 2011. Evaluation field work was conducted between November 2010 and January 2011.

2.2 Issues and Questions

Relevance

- Do the provisions and operations of the FSMA, including its four institutions and supporting authorities, continue to be relevant to federal government priorities and to INAC's strategic outcomes?

- Is there an ongoing need / anticipated future demand for the FSMA, including its institutions, as currently designed and delivered?

- Are the legislated mandates and functions of the institutions involved in administering the FSMA still relevant?

Design and Delivery - To what extent has the FSMA been implemented within the expected time frame?

- Has the FSMA established a successful governance framework, overall, and with respect to each institution?

- Are the institutions' business plans consistent with expected results and how effectively are results/outcomes measured (see Question 9)? Are the plans being implemented as intended?

- To what extent are First Nations engaged and participating as expected in the implementation of the FSMA and its institutions?

- Overall, are the activities of the FSMA institutions consistent with the Act's provisions [Note 5] such as the functions and powers for each institution?

Performance/Success - To what extent are the institutions progressing towards the achievement of expected outcomes?

- To what extent are the overall outcomes of the FSMA being achieved?

- What factors are facilitating or challenging the achievement of results?

- Has the FSMA had any unexpected impacts, positive or negative?

Performance / Demonstration of Economy and Efficiency - Are the institutions, their operations/mandates and expected outcomes in line with industry standards and best practices?

- Does the FSMA unnecessarily [Note 6] duplicate or overlap with other programs, policies or initiatives?

- What modifications or alternatives, if any, might improve the efficiency and effectiveness in the implementation of the FSMA?

- What best practices and lessons learned have emerged from the FSMA, within INAC and elsewhere that could contribute to improved delivery, performance measurement, and outcomes?

2.3 Methodology

The evaluation design took into account the need to inform the legislative review as well as recognized delays in implementation [Note 7]. Specifically:

- A greater focus was placed on identifying progress towards the achievement of results than on impacts.

- In addition to addressing Treasury Board's core evaluation issues (relevance and effectiveness), the study included questions related to design and delivery.

- Wherever possible, findings identified as affecting the implementation of the Act and its results were analyzed to determine whether they stem from factors internal or external to the Act.

- An external peer reviewer was engaged to enhance the evaluation's support for the upcoming legislative review.

2.3.1 Data Collection Strategy

The findings, conclusions and recommendations for this evaluation are based on the collection, analysis and triangulation of information derived from the following multiple lines of evidence:

Literature Review: The literature review was conducted through October and December 2010 and focussed on academic literature and other initiatives of a similar nature to address relevance, best or promising practices and lessons learned. The literature selected included peer-reviewed published literature on bond financing mechanisms, such as banks / pooled municipal bonds, the impact of economic development and improvements to quality of life, principles of good governance, change management literature and industry standards and/or principles of commercial lending. It included publications, documents published on the internet, legislation, evaluation reports of INAC programs related to economic development and other relevant program literature published by the Government of Canada. As well, the evaluation considered peer-reviewed and grey literature from the United States, Australia, New Zealand, South Africa, Peru, China, Central and Eastern European transitional economies on the topics noted above. A total of 44 documents were reviewed.

Document and File Review: This line of evidence drew on documents and files related to the overall Act, its provisions and implementation, with a specific focus on the relations between the four institutions and with INAC. A total of 42 departmental documents were reviewed between October and December 2010. These documents covered issues related to government priorities, program design, administrative data and performance. INAC's expected and actual expenditure data related to its support for the overall implementation of the Act were also included in this review. Documents and files related to the individual institutions were examined in the evaluation's case studies.

Key Informant Interviews: Interviews were conducted with 15 INAC officials between December 2010 and January 2011. These interviews focussed on the FSMA, its provisions and implementation, as well as the relations between the institutions and with INAC. Interviews were held with representatives from regional operations (7), including senior management and program officials, and other department areas (8), including Lands and Economic Development, Policy Coordination, Infrastructure, Treaties and Aboriginal Government and Strategic Policy Research.

The evaluation team employed the following scale in its analysis of this line of evidence:

- very high degree of consensus – all but one or two key informants agreed on a point;

- high degree of consensus – all but three or four of the respondents were in agreement;

- most – more than half of the respondents;

- half or roughly half – about half the respondents held a common view on an issue; and

- non-consensus comments were identified as such.

Institutional Case Studies: Four case studies were conducted to provide an in-depth review of implementation and results within each institution created under the FSMA. Site visits were made to the FNTC, FMB and FNFA offices during the first week of November 2010. Follow-up telephone interviews took place with officials during November and December. Officials from FNSI participated in telephone interviews in January 2011.

Institutional documentation was reviewed and 44 interviews were conducted with representatives from the four First Nations institutions and stakeholders associated with the FNTC (15), FMB (16), FNFA (10), and FNSI (3). Officials participating in the case studies included: Board/Commission members; institutional staff; representatives of affiliated institutions (Native Law Centre of Canada, Tulo Centre of Indigenous Economics, First Nations Tax Administrators Association, and the Aboriginal Financial Officers Association); institutional legal counsel and management consultants; representatives of the Canadian Property Tax Association, British Columbia municipal agencies, regional development corporations; and the Banking syndicate, and other subject matter experts.

2.4 Roles, Responsibilities and Quality Assurance

The analysis in this report is based largely on the work carried out by T.K. Gussman Associates Inc. and EPMRB officials. This work included document and literature reviews, key informant interviews and institutional case studies.

An Evaluation Advisory Committee was established in line with EPMRB's Engagement Policy. Committee members include representatives of INAC's Governance Branch and the four FSMA institutions. The Advisory Committee was tasked with reviewing the evaluation's draft detailed methodology report, preliminary findings and draft final report. The evaluation was able to draw upon an existing working group of INAC (PIDD) officials and FSMA institutions to form its Advisory Committee. For the most part, this allowed the evaluation to use regularly scheduled meetings of the Working Group to meet with the Committee.

In line with INAC's Quality Assurance Strategy, key deliverables were subjected to internal and external peer reviews. To enhance the evaluation's support for the upcoming legislative review, the consulting firm, Delsys Research Inc., was engaged for the external reviews.

2.5 Limitations

Limitations identified during the evaluation's design

- Performance measures, as captured by the existing RMAF, provide only limited guidance and support to the evaluation.

- A clear definition of what was required for the institutions to be considered operational as well as the expected costs and time frames for becoming operational were not well defined. Funding documents specifically identified two years of start up costs but did not clarify what activities constituted 'start-up activities'.

As such, the evaluation has adopted a working definition of 'operational' that includes whether each institution has a board of directors or commission in place, a comparison of the actual expenditures versus the planned expenditures and the extent to which each institution is delivering services in its mandated areas.

Changes to the original evaluation design and rationale

- The evaluation questions were revised slightly during the development of the study's detailed methodology report, but are consistent with the preliminary set of questions identified in the evaluation's Terms of Reference, approved by INAC's Evaluation, Performance Measurement and Review Committee (EPMRC) on June 29, 2010 (see Section 2.2, above, and Appendix A for further information).

- The evaluation's preliminary findings were reviewed by EPMRC on February 22, 2011. In response to the Committee's comments, additional research and analysis were undertaken to examine the authorities supporting implementation as well as issues related to institutional capacity building. The Committee also requested that the final report clearly present findings specific to each institution.

Challenges encountered during the implementation of the evaluation

The following limitations are noted with respect to the individual lines of evidence:

- Major limitations were encountered with the study's comparative analysis and as a result, this line of evidence was not incorporated into the final report. Research was led by BBMD Consulting and included an analysis of an INAC community level dataset for differences between FSMA scheduled communities and First Nation communities in general and interviews with two First Nation communities. Due to issues raised around the reliability and completeness of INAC's dataset and the limited number of interviewees, the evaluation team determined that the information generated by the research was not reliable / representative.

It is worth noting that the evaluation team contacted representatives from 35 communities, 33 of which either declined or chose not to respond. Similarly, First Nations declined in the past to participate in an evaluation of the implementation of the First Nations Oil and Gas and Moneys Management Act, which is also optional legislation.

- The FNSI case study was limited by the relatively small number of available written documents and the small number of key informant interviewees (i.e., three) available to participate. Written documents provided by FNSI officials were supplemented with information published by FNSI on its website and other sources.

- Findings are limited with respect to the Credit Enhancement Fund Grant, which Treasury Board Secretariat required to be considered in this evaluation. This is largely the result of the evaluation's timing and the status of the Grant (The Grant was approved under the condition that it was distributed within a one year period beginning March 28, 2010; as of February 22, 2011, a component performance measurement strategy had been approved but the funds had not yet been disbursed).

3. Findings - Relevance and Performance

3.1 Relevance

3.1.1 Addressing a Continuing Need and Role of the Federal Government

Summary of Key Findings: FSMA addresses barriers to economic development on reserve by affirming First Nations fiscal powers that are similar to local governments in areas related to the collecting of property tax revenues and accessing favourable interest rates through pooled investments and pooled borrowing regimes. FSMA also addresses longstanding issues related to the timeliness and completeness of Aboriginal statistics.

The literature and document reviews found evidence of a need for improvements in the quality of life in most First Nations and a need to reduce barriers to economic development to allow First Nations to achieve a level of well-being on a par with that of the general Canadian population. The literature showed that the lack of adequate infrastructure is one of many factors influencing the pace and success of economic development ventures. [Note 8]

A 2007 Special Study by the Standing Senate Committee on Aboriginal Peoples [Note 9] identified key barriers to Aboriginal community economic and business development as: access to capital; legislative and regulatory barriers, particularly those posed by the Indian Act making it difficult to secure loans using land and other assets as collateral; lack of governance capacity; infrastructure deficits, limited access to lands and resources; building human capital; and a fragmented federal approach to and limited funding for economic development. [Note 10]

With respect to governance capacity, the Committee commented that the ability to make good decisions requires capable governance and governing institutions. As Aboriginal people acquire increased decision-making authority over their lands and resources, there is a need to invest in governance (or institution) building. [Note 11] The report cites the FSMA along with the First Nations Land Management Act (FNLMA),the First Nations Oil and Gas and Money Management Act (FNOGMMA)and the First Nations Commercial and Industrial Development Act (FNCIDA) as recent developments in institution building in this area. [Note 12]

This evidence of relevance is further echoed in research conducted by the Institute on Governance, which has identified key elements of the First Nation governance system that, when combined, produce a degree of dysfunction in governance that is unmatched in any other jurisdiction in Canada. These elements include a lack of checks and balances, a startling number of regulatory gaps and dependence on federal government transfers (due to a lack of locally generated revenue through user fees and taxation). [Note 13] Moreover, in a roundtable discussion on how First Nations can manage their wide ranging complex government functions, John Graham argues that aggregation is a compelling option because it can increase a community's economy of scale, help separate regulator functions from service delivery and increase the pool from which core competencies and skills can be drawn. [Note 14]

FSMA can be seen as an informed response to the above needs by creating four institutions (FNTC, FMB, FNFA and FNSI) to help develop financial management capacity, and to provide regulatory oversight over First Nations that are exercising jurisdiction over the collection of property tax and accessing loans through a pooled borrowing regime. As indicated by key informants, FSMA set in motion powers (the capacity to collect taxes and ensure accountability to taxpayers), which are consistent with the kind of powers utilized by other governments, including local governments and provinces.

FSMA is also designed to address data gaps related to Aboriginal statistics in general. According to Statistics Canada, access to trusted information is fundamental in an open, democratic society to support decision making by citizens and their elected representatives. Despite the importance of statistical information to governance, Statistics Canada acknowledges that the data available for Aboriginal peoples are not timely and are incomplete compared with the data available for the general population. While the Census of Population paints a broad picture, more in-depth data from on-reserve Aboriginal surveys are needed to understand determinants and consequences of changes in areas such as early childhood development, work, education, health and housing. [Note 15] For example, the population from 22 First Nation reserves was not included in the 2006 Census due to lack of participation by communities. [Note 16]

It was widely believed by key informants that Aboriginal people are hesitant to participate in Government of Canada surveys due to a wide variety of historical and political beliefs. As a result, it is essential for there to be a First Nation-led Institution to support First Nation governments with statistical information.

3.1.2 Alignment with Government Priorities

Summary of Key Findings: FSMA aligns with federal government priorities related to the Federal Framework for Aboriginal Economic Development and INAC's Governance and Economic Development Strategic Outcomes.

FSMA aligns with the strategic priorities of the Federal Framework for Aboriginal Economic Development, a$200-million investment announced on June 29, 2009, by the Minister of Indian Affairs and Northern Development and Federal Interlocutor for Métis and Non-Status Indians and the Chairperson of the National Aboriginal Economic Development Board [Note 17]. This Framework was seen as building on the 2006 Advantage Canada long-term economic plan for Canada's overall prosperity, benefitting from the Standing Committee's 2007 report, and fulfilling the Budget 2008 commitment to launch a new approach to Aboriginal economic development. [Note 18]

The Federal Framework for Aboriginal Economic Development strategic priorities are:

- Strengthening Aboriginal entrepreneurship;

- Developing Aboriginal human capital;

- Enhancing the value of Aboriginal assets;

- Forging new and effective partnerships; and

- Focusing the role of the federal government.

The implementation of the Framework was to include investments in new measures to support these priorities by:

- Leveraging greater access to commercial capital;

- Investing in efforts to promote Aboriginal procurement;

- Supporting Aboriginal participation in resource development opportunities; and

- Accelerating the economic use of lands set aside through specific claims settlements.

FSMA aligns with enhancing the value of Aboriginal assets by enabling First Nations to collect property taxes on reserve and use those revenues to access affordable loans through a pooled borrowing regime. It also aligns with developing Aboriginal human capital by helping First Nations to improve financial management through the FMB and through the First Nation Certificate Programs in Tax Administration and Applied Economics, which are delivered through a partnership between the Tulo Centre of Indigenous Economics, Thompson Rivers University and FNTC. [Note 19]

Under INAC's Program Activity Architecture, support for the implementation of the FSMA and its institutions falls within the Governance and Institutions of Governance Program Activity, which supports INAC's Strategic Outcome: The Government – Good governance, effective institutions and co-operative relationships for First Nations, Inuit and Northerners. This program activity supports legislative initiatives, programs and policies, and administrative mechanisms that foster and support legitimate, stable, effective, efficient, publicly accountable, and culturally relevant First Nation and Inuit governments.

There is a clear link between INAC's Strategic Outcome, The Government and the objectives and results as stated in the Terms and Conditions for Contribution to First Nation Institutions for the purpose of enhancing good governance, and the Program Overview for the Contribution. Moreover, they position effective governance as laying the foundation for economic development and growth, which underpin the long-term objectives and activities of the FNTC, FMB and FNFA as reported in the institutions' annual reports and corporate plans. Similarly, a clear link was found between the FSMA and the strategic outcomes of 'economic development' and 'prosperity' reported in INAC's Report on Plans and Priorities.

3.2 Performance: Progress and Unexpected Impacts

As noted earlier in the report, it is difficult to assess the overall impact of FSMA due to the timing of the evaluation as well as with challenges with performance measurement. This section highlights evidence found respecting the overall implementation and results of FSMA as well as promising developments, not envisioned during the planning stages.

3.2.1 First Nations Participation

When the FSMA was enacted, 103 First Nations had Property Tax By-laws under s.83 of the Indian Act. As of January 1, 2008, 25 of these First Nations passed Band Council Resolutions in order to be added to the FSMA schedule. Eight other non-taxing First Nations were also added to the FSMA schedule at that time. [Note 20] As of February 2011, 60 First Nations were scheduled. Table 2 summarizes the participation levels each year since the original 33 First Nations were scheduled under the Act.

| 2007/08 | 2008/09 | 2009/10 | 2010/11 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| First Nations | 33 | 45 | 55 | 60 |

Source: Canada Gazette

Table 3 presents the FSMA-scheduled First Nations by province. The majority of the FSMA-scheduled First Nations (45) are located in British Columbia and the remaining 15 are spread throughout Canada. Respondents noted that the reason for the distribution of scheduled First Nations is because most First Nations who historically collected property tax are located in British Columbia. They also noted that participation from other regions is expected to increase once FSMA is expanded to include other revenues. The total registered First Nation population currently under FSMA is approximately 46,000 individuals (six percent of the total registered population). [Note 21]

| BC | AB | SK | MB | ON | QC | NB | NS | PEI | NFL | YK | NWT | NUN | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FSMA | 45 | 1 | 6 | 1 | 3 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 60 |

| Total # of FNs | 198 | 47 | 70 | 63 | 140 | 39 | 15 | 13 | 2 | 3 | 18 | 26 | 0 | 634 |

| FSMA FNs as % of all FNs |

23% | 2% | 7% | 2% | 2% | 0% | 27% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 9% |

Sources: Canada Gazette

It should also be noted that treaty and self-governing First Nations require adaptation regulations in order to be scheduled under the Act. Currently, two First Nations, Tsawwassen (treaty) and Westbank (self-governing), are working with INAC on adaptation regulations. Tsawwassen was originally added to the FSMA schedule in December 2007, but when the Tsawwassen First Nation treaty took effect on April 3, 2009, the First Nation was no longer defined as a 'band' under the Indian Act and, consequently, was no longer eligible to be scheduled under the FSMA. [Note 22]

First Nations in the Yukon and Northwest Territories who have not settled self-government or land claim agreements and do not have reserve lands cannot access the FSMA.

The following additional positive unexpected impacts were identified by evaluation participants:

- There is continued growth in the number of First Nations collecting property tax under s.83 or the FSMA. Eighty-four percent of First Nations (21 out of 25) that have started collecting property tax since 2007 chose the FSMA over s.83.

- Local governments are reported to be more willing to partner with First Nations on economic development. For example, Shuswap First Nation is fully integrated with regional governments in the delivery of services and in capitalizing on economic potential. Specifically, the First Nation operates the regional airport and water infrastructure that serves the whole region and the Regional District provides fire services to the whole region. [Note 23] Interviewees claimed that these sorts of arrangements are possible because the Regional District has confidence in that the First Nation can uphold its obligations in such service agreements.

This can also be seen in the District of West Vancouver (DWV) strategic plan, which identifies the following priority: "Attention to intergovernmental relations, especially working with our Member of the Legislative Assembly and Member of Parliament, the Squamish Nation, and North Vancouver City and District. We have been served well by our proactive approach and if we are to manage properly, we need to be ready for legislative change and prepared to coordinate and perhaps amalgamate services." [Note 24] During an interview for the evaluation, the Mayor of the DWV corroborated observations by FMB officials that FSMA is facilitating partnerships between Squamish Nation and the DWV by granting them fiscal powers that are similar to other levels of government. - The FMB reported that one First Nation community is using FMB products to get favourable rates from private lenders.

- An agreement in principle to use FMB Certification process as a proxy in the INAC General Assessment.

The following four sections present the evaluation's findings related to implementation and performance (success) in each of the four FSMA institutions. Findings with respect to efficiency and economy are examined in Section 8.

4. Findings - First Nations Tax Commission

4.1 Ongoing Need and Relevance of the Institutional Mandates

Summary of Key Findings: The FNTC's mandate under the FSMA is relevant to facilitating third-party investment in reserve property by increasing the transparency and fairness of the tax regime. FNTC is essential to property tax regimes on reserve as it is responsible for administering Section 83 of the Indian Act as well as FSMA part 2.

Under Section 29 of FSMA, the purposes of FNTC are to:

- ensure the integrity of the system of First Nations real property taxation and promote a common approach to First Nations real property taxation nationwide, having regard to variations in provincial real property taxation systems;

- ensure that the real property taxation systems of First Nations reconcile the interests of taxpayers with the responsibilities of chiefs and councils to govern the affairs of First Nations;

- prevent, or provide for the timely resolution of, disputes in relation to the application of local revenue laws;

- assist First Nations in the exercise of their jurisdiction over real property taxation on reserve lands and build capacity in First Nations to administer their taxation systems;

- develop training programs for First Nation real property tax administrators;

- assist First Nations to achieve sustainable economic development through the generation of stable local revenues;

- promote a transparent First Nations real property taxation regime that provides certainty to taxpayers;

- promote understanding of the real property taxation systems of First Nations; and

- provide advice to the Minister regarding future development of the framework within which local revenue laws are made.

The FNTC's mandate was found to be critical to the implementation of FSMA as a whole because it creates certainty and transparency in how tax systems operate on reserves. First Nations can collect taxes under Section 83 of the Indian Act, but there is very limited regulation and limited mechanisms to ensure representation of taxpayers who are not band members (thereby acting as a disincentive to non-member investments in reserve land). This is a significant point because most taxpayers are not band members. FSMA addresses this issue by requiring First Nations to ensure taxpayer representation, including an opportunity for taxpayers to make representation to the Commission prior to approval of local revenue laws. Furthermore, FSMA has granted FNTC administrative tribunal powers "to prevent, or provide for the timely resolution of disputes in relation to the application of local revenue laws."

In addition to its responsibilities under FSMA, FNTC is responsible for advising the Minister on property tax by-laws under Section 83 of the Indian Act and therefore, all First Nations who collect property tax are regulated and supported by the FNTC.

4.2 Implementation

Summary of Key Findings: Based on an analysis of FNTC's governance framework, use of resources, and the extent to which each institution is delivering services in its mandated areas, the evaluation found that the FNTC is fully operational and implementing its responsibilities under FSMA as intended. Additionally, through FNTC, First Nations have generated over $170M in local revenue ($70M of which is under FSMA and $100M under s.83).

4.2.1 Governance Framework

The FNTC has established an appropriate governance framework in line with Part 2 of the FSMA. The institution is a shared-governance corporation [Note 25]; the Minister is responsible for appointing nine commissioners, including the Chief Commissioner and Deputy Chief Commissioner, through the GIC process and the Native Law Centre of the University of Saskatchewan is responsible for appointing one commissioner. Of the ten commissioners, one must be a taxpayer using reserve lands for commercial, one for residential and one for utility purposes.

The Commission has been in place since July 2007 when the last appointment occurred. It is currently comprised of ten representatives from all regions of the country, except for the territories.

Rules of Procedure and Governance have been established for the Commission that cover areas related to the purposes and service areas, proceedings, panels and committees, the Chief Executive Officer and Secretariat, law review, statutory requirements, financial management and reporting. The evidence suggests that decision-making processes established by the Commission consider both the interests of First Nation governments and those of property taxpayers. For example, under the policy development service area, the Rules of Procedure and Governance state that the objective is to develop and implement effective Policies and Standards that support sound administrative practices and increase First Nation and taxpayer confidence and certainty in the integrity of the First Nation local revenue system. [Note 26]

Interviewees reported that this governance structure allows for appropriate independence in decision making as well as appropriate oversight from the Government of Canada.

The literature review concludes that the Commission meets the governance principles of leadership and stewardship [Note 27]/ legitimacy and voice [Note 28]. As well, the review concluded that the committees established by the Chief Commissioner to support the Commission's work meets the governance principle of accomplishment or performance. The committees that have been established are:

- Executive Management Committee;

- Management Committee;

- Audit Committee;

- Section 83 Rates Committee;

- Education and First Nation Tax Administrators Association Committee;

- International Relations Committee; and

- First Nations Gazette Editorial Board.

4.2.2 Expenditures

As shown in Table 4, FNTC's total expenditures were $26.1M and expenditures in each year closely parallel planned expenditures.

| Expenditures | 2006-2007 | 2007-2008 | 2008-2009 | 2009-2010 | 2010-2011 | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Planned | 2,975 | 5,343 | 4,490 | 4,500 | 4,510 | 21,818 |

| Actual | 3,530 | 5,492 | 5,775 | 5,477 | 5,918 | 26,192 |

| Difference | (555) | (149) | (1,285) | (977) | (1,408) | (4,374) |

Source: Planned expenditures are abridged from funding documents. Actual expenditures are from FNTC financial records.

Note: 2006/07 and 2007/08 include money transferred to the Indian Taxation Advisory Board (FNTC's predecessor) as part of transitioning to FNTC

4.2.3 Activities

The FNTC is delivering all services for which it was mandated. The FNTC's move to becoming fully operational was supported by the existing foundation of the Indian Taxation Advisory Board that had been in operation for 15 years. Additionally, a number of First Nations were committed to being scheduled well before the FSMA's enactment.

The FNTC maintains a head office on the reserve lands of the Kamloops Indian Band and an office in the National Capital Region in accordance with s.26 of the Act. Both offices provide Commission services to FSMA and s.83 First Nations with a regional focus on service delivery. The FMSA registry is located at the head office and the s.83 registry is in the National Capital Region Office. The Commission is supported by 22 full time equivalents and structured around six business lines that report to the Chief Executive Officer. To support its operations, FNTC has established policies and procedures for information management access to information and privacy. It has also developed a Public Input Policy for greater stakeholder involvement in the development and improvement of FNTC policies, procedures, standards, and services.

FNTC has created and implemented a corporate plan for each year of operations and annual reports on the achievement of the objectives defined by the corporate plans. It also continues to maintain a registry of every approved FMSA law, a registry of s.83 by-laws and, through the Native Law Center of Canada, it publishes the First Nations Gazette [Note 29] two times per year. The Gazette includes all s.83 by-laws and FSMA laws. Furthermore, FNTC created and maintains a website and publishes newsletters.

FNTC has completed ten standards pursuant to s.35 of the FSMA (including expenditure, property assessment, property taxation, service tax, annual tax rates, development cost charges, borrowing, borrowing approval criteria, taxpayer representation to council, and submission of information for Section 8 requirements). The completed policy framework includes the following policies concerning: FSMA Registry, First Nations Gazette publication, public input, and dispute prevention/resolution. It has also developed a work plan for law development and sample representation plans, notices, letters respecting submission of property tax laws, letters respecting submittal of amending laws.

FNTC has also developed 23 sample laws, including: taxation, assessment, rates, expenditure, tax for the provision of services, development cost charges, taxpayer representation to council, long term borrowing law, and long term borrowing agreement law. This includes region-specific property tax law samples that have also been developed for First Nations in eight provinces. FNTC has developed and is implementing procedures for reviewing and approving FSMA laws (after the initial local revenue law is approved, First Nations require the annual approval of assessment and rates laws).

As a part of the regulatory framework supporting property taxation under Section 83, the FNTC developed new policies related to by-laws for property tax, assessment, annual rates, and annual expenditures as well as sample by-laws for property tax, assessment, annual rates, expenditures, financial management, telephone company by-laws, and business licensing by-laws.

Thirty-nine First Nations are currently collecting tax under FSMA and 102 First Nations have enacted by-laws under s.83.

FNTC has also worked with the Tulo Centre of Indigenous Economics [Note 30] and in partnership with Thompson Rivers University to develop and deliver certification programs in applied First Nation economics and First Nation Tax Administration.

Table 5 summarizes some of the activities that the FNTC has undertaken since it became operational. It is indicative of the level of effort invested by FNTC in order to support First Nation decision making around becoming scheduled under the Act.

| 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| National Meeting – First Nation Tax Authorities |

1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| FSMA Presentations / Meetings | 38 | 49 | 61 | 48 |

| Property Tax Presentations to First Nations New to Taxation |

5 | 9 | 9 | 14 |

| FSMA Band Council Resolutions Received Subsequent to a Property Tax Presentation |

1 | 3 | 3 | 2 |

| FSMA Band Council Resolutions Received for First Nations New to Taxation |

9 | 6 | 4 | 9 |

| FSMA Laws Approved | 0 | 81 | 90 | 69 |

| s.83 By-laws Recommended for Approval | 104 | 64 | 61 | 40 |

Source: FNTC, November 2010 (update March 2011).

Note: FNTC reports on a calendar year cycle and as such the information in this table is presented under calendar years.

Alignment with Best Practices: First Nation property tax systems and laws under the FSMA were found to be consistent with provincial and local government property tax best practices. One objective of the tax system is to harmonize on a regional basis and the FNTC sample laws are drafted to reflect regional variation.

Respondents also noted that each First Nation has unique needs and reasons for being scheduled under the FSMA, working with the FNTC sample laws is a cost-effective approach because it provides framework that can be adapted to respect First Nation specific requirements.

4.3 Results